Over the years, I’ve received numerous letters and emails from readers telling me how much they enjoy reading my work; they have also expressed interest in knowing more about my family. And touring and presenting, the questions I’m most frequently asked include: How can you remember so many details about the past? When did you start writing? What motivates you to write? What is the most important thing readers can learn from reading your work?

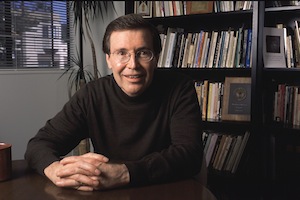

Over the years, I’ve received numerous letters and emails from readers telling me how much they enjoy reading my work; they have also expressed interest in knowing more about my family. And touring and presenting, the questions I’m most frequently asked include: How can you remember so many details about the past? When did you start writing? What motivates you to write? What is the most important thing readers can learn from reading your work?Guest Blogger: Francisco Jiménez

Over the years, I’ve received numerous letters and emails from readers telling me how much they enjoy reading my work; they have also expressed interest in knowing more about my family. And touring and presenting, the questions I’m most frequently asked include: How can you remember so many details about the past? When did you start writing? What motivates you to write? What is the most important thing readers can learn from reading your work?

Over the years, I’ve received numerous letters and emails from readers telling me how much they enjoy reading my work; they have also expressed interest in knowing more about my family. And touring and presenting, the questions I’m most frequently asked include: How can you remember so many details about the past? When did you start writing? What motivates you to write? What is the most important thing readers can learn from reading your work?

When I’m asked how I came to illustrate Patricia Hruby Powell’s Josephine: The Dazzling Life of Josephine Baker (Chronicle Books 2014), my most direct answer is that my agent Steven Malk shared the manuscript with me, after being approached by editors at Chronicle. The more magical response would be that Josephine Baker’s life was an inspiration to me long before I read Powell’s text.

When I’m asked how I came to illustrate Patricia Hruby Powell’s Josephine: The Dazzling Life of Josephine Baker (Chronicle Books 2014), my most direct answer is that my agent Steven Malk shared the manuscript with me, after being approached by editors at Chronicle. The more magical response would be that Josephine Baker’s life was an inspiration to me long before I read Powell’s text.

Not long after my dad died, just after Christmas in 1999, I found myself in the throes of intense grief. I had experienced loss before. Grandparents had passed away. Friends had left me, too. But I had never felt the kind of profound sadness that engulfed me when my father died. It caused my knees to buckle and for months I felt like I was slogging through quicksand, each step muddier than the one before it.

Not long after my dad died, just after Christmas in 1999, I found myself in the throes of intense grief. I had experienced loss before. Grandparents had passed away. Friends had left me, too. But I had never felt the kind of profound sadness that engulfed me when my father died. It caused my knees to buckle and for months I felt like I was slogging through quicksand, each step muddier than the one before it.

For seven years, I’ve been sharing the stories of the many incredibly talented Native artists, writers, fashion designers, and entrepreneurs across North America on my blog “Urban Native Girl” and the online magazine I co-founded, Urban Native Magazine. So when Mary Beth Leatherdale came to me with the idea to create an anthology for youth featuring contemporary Native writers, artists, and teens talking about their experiences growing up Indigenous, I was thrilled.

For seven years, I’ve been sharing the stories of the many incredibly talented Native artists, writers, fashion designers, and entrepreneurs across North America on my blog “Urban Native Girl” and the online magazine I co-founded, Urban Native Magazine. So when Mary Beth Leatherdale came to me with the idea to create an anthology for youth featuring contemporary Native writers, artists, and teens talking about their experiences growing up Indigenous, I was thrilled.

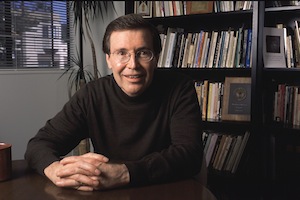

I enjoy writing in the first person. I feel it gives readers immediate insight into a novel’s protagonist; from the beginning of the story they’re inside the head that person—with all the confusion and clarity that it entails. So, when I begin to write a book, I simply sit in a not-too-quiet place (usually the library) and have an internal conversation with whomever it is that’s narrating the work, and I start taking dictation. (Old-timer’s term, look it up.) It’s a fascinating process because so often I learn from this character that the tale I’m set on telling is all wrong.

I enjoy writing in the first person. I feel it gives readers immediate insight into a novel’s protagonist; from the beginning of the story they’re inside the head that person—with all the confusion and clarity that it entails. So, when I begin to write a book, I simply sit in a not-too-quiet place (usually the library) and have an internal conversation with whomever it is that’s narrating the work, and I start taking dictation. (Old-timer’s term, look it up.) It’s a fascinating process because so often I learn from this character that the tale I’m set on telling is all wrong.

For me, it was the sheer number of fields in which Roget developed a working knowledge, and in which he also had significant influence. Roget was interested in just about everything and wrote papers, articles, and books on subjects ranging from botany to mathematics and optics to public health. Today, when most people super-specialize in a field or a skill set, this may seem unfocused. But in Roget’s time, when there was no such thing as a professional scientist, this broad intellectual life was encouraged and admired.

For me, it was the sheer number of fields in which Roget developed a working knowledge, and in which he also had significant influence. Roget was interested in just about everything and wrote papers, articles, and books on subjects ranging from botany to mathematics and optics to public health. Today, when most people super-specialize in a field or a skill set, this may seem unfocused. But in Roget’s time, when there was no such thing as a professional scientist, this broad intellectual life was encouraged and admired.