TeachingBooks is delighted to welcome author Eugene Yelchin as our featured guest blogger this month.

Each month, we ask distinguished authors or illustrators to write an original post that reveals insights about their process and craft. Enjoy!

Once in Moscow, a KGB spy…

by Eugene Yelchin

I was still a kid when my parents’ friend Natasha married a KGB spy. We lived in Leningrad but Natasha’s wedding took place in Moscow, so we had to take a train. The marriage ceremony was boring, but the reception was not. The groom’s swanky private apartment was in a government building: it had three bedrooms. I had never been to an apartment this big before. And I had never tasted any of the delicious treats that crammed the tables. These were Western foods purchased at a special KGB supermarket forbidden to regular citizens.

After several hours of toasting the newlyweds, clinking glasses, singing, shouting and laughing, the dinner ended. The women got up and huddled in the kitchen. The men remained at the table. I stayed put, too, the only child in the room.

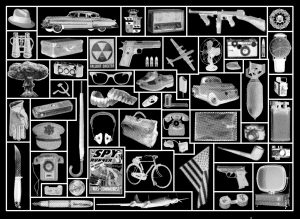

The groom’s colleagues were speaking in Russian, but I could not understand what they said. I heard phrases like chicken feed, dead drop, and pocket litter, but what did they mean? Then Natasha’s groom, red-faced and liquored up, brought out his new handgun, a 6P9 with a silencer attached, and told a story I could not follow beyond that it took place in West Berlin and fast cars were involved.

The groom’s colleagues were speaking in Russian, but I could not understand what they said. I heard phrases like chicken feed, dead drop, and pocket litter, but what did they mean? Then Natasha’s groom, red-faced and liquored up, brought out his new handgun, a 6P9 with a silencer attached, and told a story I could not follow beyond that it took place in West Berlin and fast cars were involved.

Mom was in the kitchen with the women, and Dad, who was also drunk, fell asleep on the couch. Under the cover of tobacco smoke (the KGB spies smoked only American cigarettes), I was afraid to move lest they notice me eavesdropping. Beside me, an elderly fellow sat motionless and silent, as if he too did not want to be noticed. But he was better at being invisible than I was. Thin and ashy, he seemed to blend in with the wallpaper behind him. His spectacles, which had a wad of dirty tape around the bridge of the frame, concealed his eyes so that I could not tell if he was looking at me. He was so shabby that I wondered why he was at this fancy wedding. I knew for certain that he was not a spy with a 6P9 holstered under his armpit so I decided to ignore him.

I left Moscow with my family in the morning, but by the following night in Leningrad I was eavesdropping again. My entire family, all five of us, shared one tiny room in an overcrowded communal apartment. My parents’ bed stood a couple of feet away from my canvas cot (stuck under the dinner table for the lack of space). I could hear my mom and dad whisper in the dark about Natasha’s wedding guests. I nearly fell off my cot when I heard Dad telling Mom that the unkempt fellow in the spectacles was a legendary spy, highly decorated for his service to the KGB. For 30 years that man was what is called a sleeper. His job was to pass the clandestine information from one Soviet agent to another, while pretending to be a Catholic priest in Mexico City.

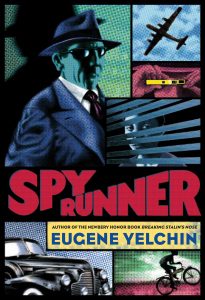

Some years later Natasha divorced her own KGB spy after he threatened her with his 6P9 pistol, and I left Russia for the United States. I forgot all about the man in the spectacles until I began researching for my middle grade novel Spy Runner (Holt, Feb. 2019). My research included memoirs and biographies of defected Russian spies and retired CIA operatives, spy manuals and declassified KGB documents, as well as Cold War training films. It was while viewing recently unearthed footage of the British double agent Kim Philby (after his defection behind the Iron Curtain), that I thought I saw the shabby man in the taped spectacles again. In the grainy video, Philby stood at a podium addressing the members of the East German spy agency Stasi, and it looked to me like the fellow from Natasha’s wedding was sitting beside the podium.

Some years later Natasha divorced her own KGB spy after he threatened her with his 6P9 pistol, and I left Russia for the United States. I forgot all about the man in the spectacles until I began researching for my middle grade novel Spy Runner (Holt, Feb. 2019). My research included memoirs and biographies of defected Russian spies and retired CIA operatives, spy manuals and declassified KGB documents, as well as Cold War training films. It was while viewing recently unearthed footage of the British double agent Kim Philby (after his defection behind the Iron Curtain), that I thought I saw the shabby man in the taped spectacles again. In the grainy video, Philby stood at a podium addressing the members of the East German spy agency Stasi, and it looked to me like the fellow from Natasha’s wedding was sitting beside the podium.

Anxiety I had not felt since I left Russia filled me. My fascination with spies had disappeared with my childhood. In my last years in the Soviet Union, I was no longer charmed by spies. In fact, I was always worried that a KGB spy might be within earshot. A careless word about our atrocious living conditions, lack of food, or a joke about Communist Party leadership could get us in awful trouble. Planted in communal apartments, at places of employment, in high schools, colleges, theatre companies, orchestras, on sports teams or public transportation, invisible spies were everywhere. Most did it for money, but many out of the conviction that Soviet citizens must remain loyal and obedient to the Communist Party.

The closer I studied Philby’s footage, the more unease I felt. Not only the man sitting beside the podium but every man in attendance, including Philby himself, could have been that fellow from Natasha’s wedding. Thin, ashy, and bespectacled, all these spies had the same unkempt appearance that bordered on invisibility. I could no longer trust my judgment. The only way to confront my anxiety was to carry it into my writing.

The closer I studied Philby’s footage, the more unease I felt. Not only the man sitting beside the podium but every man in attendance, including Philby himself, could have been that fellow from Natasha’s wedding. Thin, ashy, and bespectacled, all these spies had the same unkempt appearance that bordered on invisibility. I could no longer trust my judgment. The only way to confront my anxiety was to carry it into my writing.

In Spy Runner suspicion and mistrust cloud the young protagonist’s perception. He barrels toward a shattering discovery that no one, including his mother, is who they seem. In essence, Spy Runner could be called a book for our post-truth historical moment. The spies of my youth, including the untidy man who posed as a Catholic priest, now seemed like child’s play. Today, fake photographs, fake videos, fake websites, and fake social media cast doubt on everything we hold as true.

If Spy Runner alerts young readers to clandestine methods by which one state asserts influence over the other, then my hope is that today’s youth might be better equipped to make sense of what is happening in the United States today.

Listen to Eugene Yelchin discuss the rewriting of truth and Spy Runner

Hear Eugene Yelchin pronounce his name and explain its backstory

Discover more resources for books written by Eugene Yelchin

Leave a Reply