Sharing Korean Culture with a Halloween Twist

My favorite question to ask on a school visit for The Goblin Twins (Random House, 2023) is “What are some mythical creatures you know?” As you can imagine, I receive many exuberant answers – Unicorns! Fairies! Mermaids! Werewolves! Dragons!

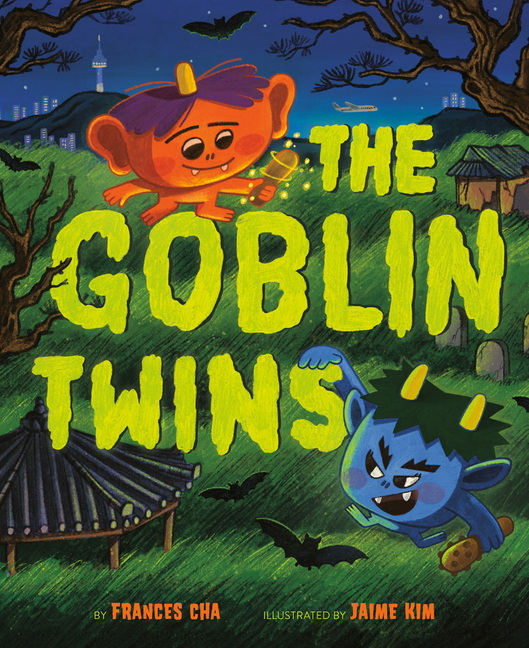

Cue my introduction: “In Korea, where I grew up, one of our most famous mythical creatures is the dokkaebi – a cross between a goblin and a spirit – and stories about them have been told for thousands of years.” I love seeing children’s excited curiosity learning about magical creatures from another culture and they start asking torrents of wonderful questions about them.

In folklore, dokkaebi are famous for several traits – they like to scare or play tricks on people, they like to live in abandoned houses or graveyards, they use their magic clubs to conjure gold or silver, and they wear hats that make them invisible.

I had originally been researching dokkaebi due to a family story dating back several decades. While children’s tales tend to show dokkaebi largely being either foolish or pranksters, adult tales about dokkaebi tend to run quite dark. In this family story, my mother and my uncle knew a family that had been rumored to serve a dokkaebi for several generations. The dokkaebi had brought them unimaginable wealth and calamitous ruin, and then had disappeared with the last member of that family. Deep into my research, I had dokkaebi on the brain and was also reading a lot of children’s tales about these goblins.

During this time, my two young daughters were in school in New York and were the only Korean children in their grades. Their friends were curious about Korea and were not familiar with Korean culture. I wished I could gift their friends books that introduced a fun aspect of Korean culture, and these two themes ran together in my brain, planting the seed for The Goblin Twins.

My intention with this children’s book was to not only wonder what dokkaebi – who were often considered both ancient and immortal – would think of the modern age, but also, in particular, what they would think of the West’s celebration of Halloween, which is not celebrated in Korea. So many characteristics of dokkaebi match the spookiness of the holiday, and I imagined two “younger” dokkaebi hearing about this strange place where people like being scared and going to haunted houses and wanting to go check it out for themselves.

I also wanted to make the story as funny as possible. A comment by a bookseller at a beloved children’s bookstore made a deep impression on me. She said, “I’m so glad you are making your book so funny, because so many BIPOC writers’ books are so sad.” While I certainly want to write my share of sad stories about history and social issues, I also want to add to the humor spectrum of representation, as those are the books we choose over and over at bedtime in our house.

In the first Goblin Twins book, I was interested in shifting perspective. To so many people living in America, New York City is considered the busiest, crowded city of towering skyscrapers. And yet, whenever I landed in New York after months of being in Asian cities, I was always struck by how spacious and leisurely NYC seemed after Seoul or Hong Kong or Tokyo! It was so much fun to work in jokes that would appeal to not only children but to adults as well. And as I was teaching a fiction workshop at a university at the time of writing, my classes often discussed subversion of expectation in fiction – and so of course I had to work in a “scary” twist at the end!

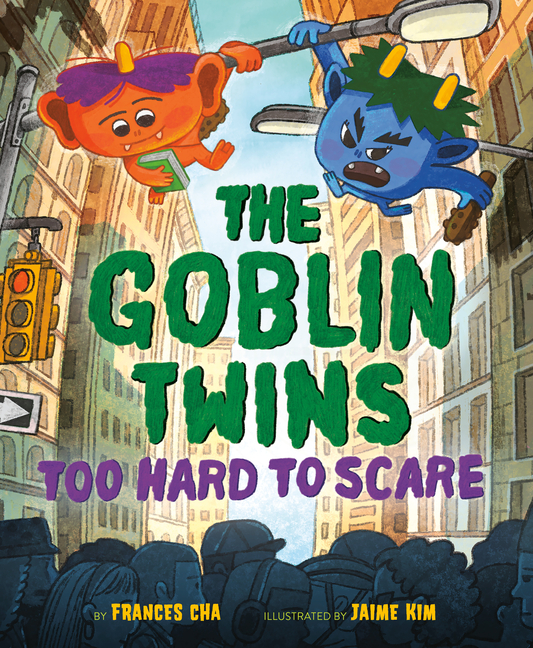

In the second book, The Goblin Twins: Too Hard to Scare (Random House, 2024), there was a more pronounced focus on the two dokkaebi brothers’ contrasting personalities. One is an introvert who wants to stay in and read, the other is an extroverted prankster who wants to wreak havoc. In my fiction workshop, another main tenet we discuss often is thwarted desire. Kebi – used to terrorizing Koreans throughout six centuries of pranks – is trying to terrorize New York City, but New Yorkers don’t even register his existence, let alone feel scared! Doki, the introvert, ends up putting aside his desire (to read) and humors his brother. Sacrifice doesn’t feel like sacrifice when it’s for someone you love.

The second book was also inspired quite literally by observing the relationship between my two children. I often notice a lot of sacrifice being made on both sides and these little glimpses of learning through small acts of consideration have been some of the most amusing and heartwarming experiences of parenting. My older daughter – age 8 at the time of the writing of this book – always wants nothing more than to read all day and all night, but my younger daughter – not yet a strong reader then – would beg her to play. My older daughter would then give a small sigh and put her book aside and play with her sister. Likewise, when it was my younger daughter’s turn to pick a song or a destination or a meal, she would choose what her older sister would want, instead of what she wanted herself, mirroring her sister’s consideration.

At my school visits, I am always amazed at how perceptive the children are at understanding beyond what I am interested in exploring through writing. They love the idea of a different perspective, and comprehending something they take for granted through someone else’s eyes and history. I feel so lucky to be able to interact with my readers this way, and to share their wonder.

Listen to a Meet-the-Author Recording for The Goblin Twins

Listen to Frances Cha talk about her name

Discover a curriculum guide to help feature The Goblin Twins for your students

Explore Frances Cha’s author page on TeachingBooks

Text and images are courtesy of Frances Cha and may not be used without express written consent.

Leave a Reply