From Teaching to Writing

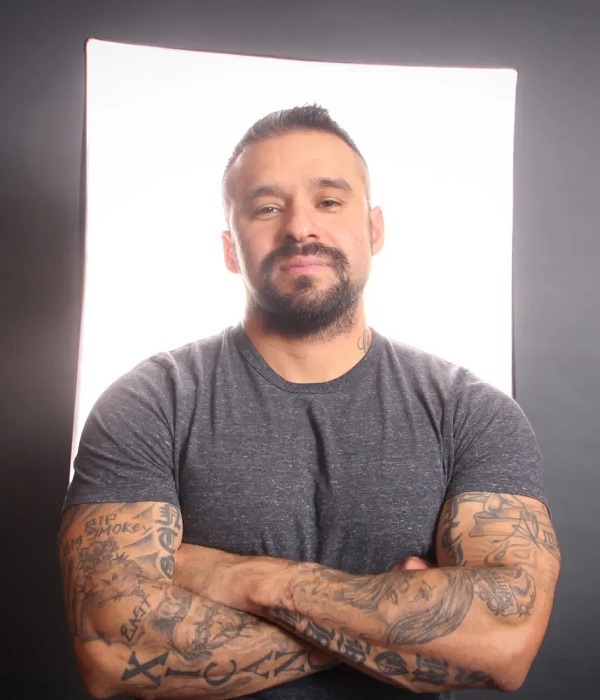

TeachingBooks asks each author or illustrator to reflect on their journey from teaching to writing. Enjoy the following from Joe Jiménez.

Can a School Project Really Change Your Life?

by Joe Jiménez

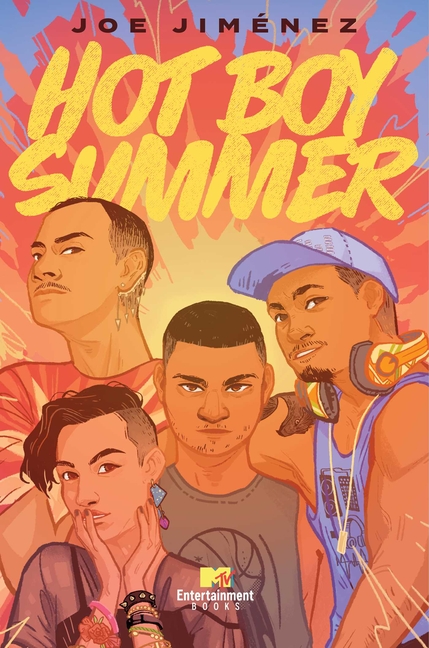

My most recent book is Hot Boy Summer (Simon & Schuster, 2024), a young adult novel about four very gay BFFs from San Antonio, Texas—Mac, Mikey, Flor, and Cammy—all joining together the summer before their senior year to bond over breakfast tacos, pop music remixes, and their mutual love of the iconic Ariana Grande and international drag superstar Valentina. It’s giving very high school friend group drama, with explosive group chats, excessive hashtags, and a character fluent in the art of keeping receipts. So, how exactly do Mac, Mikey, Flor, and Cam all become friends?

In the novel’s opening chapter, Mac, Mikey, Flor, and Cam are presenting their final exam projects for their eleventh-grade English class. It’s the last day of junior year, and as much as the students are exhausted by the year, they are equally, if not so much more, excited by summer. In regard to emotional autobiography, this is a very familiar feeling.

The characters’ teacher Mr. Villarreal designs a project-based assessment that tasks each student with writing a letter to a celebrity or public figure who the student wants to do something, to continue doing something, or to not do something. Villarreal instructs his students to write “the best letters of your lives” and that the composition needs to demonstrate an understanding of ways rhetorical techniques can be used to convey messages, which was the focus of their AP Language and Composition coursework. The four characters become friends because Florencio shares a letter that gives his peers something to connect with.

In my twenty years of classroom experience, I’ve seen some of the most meaningful student learning expressed via projects such as the letter Flor writes. In Hot Boy Summer, as students present their letters to the class, Flor bravely reads his letter to international drag superstar Valentina, discussing the sense of hope and belonging that people like Valentina give so many of us who are experiencing isolation, loneliness, and hate on school campuses and at home. As the second-ranked student in his class, Flor definitely understands the assignment, effectively demonstrating his control of authorial choices such as parallel structure, colloquialisms, and shift. Just as importantly, the letter provides Flor and his classmates with an opportunity to consider global issues and human concerns.

Here, a teacher-made, project-based assessment generates an opportunity for learning that a multiple-choice test, which certainly has its own merits, would not be able to do. In this way, I wanted HBS to serve #classroomrealness because in my French Vanilla Fantasy, more classrooms today would serve students the way my old-school, small-town Texas English teachers taught me—projects where we applied and synthesized our learning, drafts of those projects with specific and meaningful individualized feedback, and discussions to show what we’d learned rather than test after test to collect data, make spreadsheets, and prove to someone that teachers are, in fact, doing our jobs and that students are indeed learning. For what it’s worth, yes, any of us, with guidance and training, if needed, could generate a spreadsheet using the data Flor’s letter presents regarding his mastery of rhetorical strategies like structuring an argument, appropriately utilizing informal diction, and employing a rhetorical shift.

Maybe I’m a quasi-traditionalist when it comes to the need for more project-based assessments that don’t center reading passages and multiple-choice items in our English classrooms. Maybe I was just blessed with really, really good small-town teachers, women whose classroom management prioritized respect, hard work, and skills-building, no matter how much or how little money their students came from. Maybe as I near the end of my teaching career, I’ve become more reflective about what’s happening on campuses like mine, about right choices and wrong choices I’ve made when it comes to instruction.

What I fear, though, is that around the country campuses with at-risk or falling-behind student populations so deeply focus on data-based gains that we put aside not only the importance of real-world applications of student learning in ELA but also, too, the human concerns students carry like the need for joy, hope, and belonging, which novels, short stories, dramas, and poems and the projects we create in response to these texts so often stir within us.

Of course, many of us are already doing the work of joy, hope, and belonging in our classrooms, and here, I acknowledge that in my own classroom I can and should do more. Truthfully, in the few years after the Pandemic, I have succumbed to pressure—both in top-down administrative directives as well as self-imposed duress—to focus almost exclusively on preparing students for college-readiness exams and to constantly be hyper-aware of campus ratings, school report cards, and making gains to compensate for recent losses. Subsequently, I have limited my students with the imbalance I create by focusing so heavily on easily quantifiable data and therein not creating the SIOP Learning Menus and choice-driven projects we used to create on my campus years ago so that students could show us in so many ways all that they’d learned.

And while I say this, I recognize also the very real dilemma so many schools like mine face. Due to brutal budget cuts, we won’t have a librarian on our campus next year, and we are losing more than a dozen teachers—for those of us remaining, our course loads and class sizes balloon. Again, teachers and students will be asked to accomplish more with less. So, why emphasize project-based assessments with all this drama happening around us?

In so many ways, the world is still what we make of it.

In times of constraint, our brains can freeze up and maintain the status quo, or we can allow our brains to be brains and respond with novelty and imaginativeness, much like a poem-maker does when crafting a lipogram or a sonnet. Here, I’d be silly not to mention my 8th grade English teacher Mrs. Rita Hedtke at Leon Taylor Junior High School in Ingleside, Texas, way back in 1988, whose assessment after teaching our class elements of fiction—including plot, conflict, characterization, dialogue, and description—was for each of us to compose an original short story to show her what we’d learned. It was the first story I’d ever written.

In many ways, I think now that I write novels because of Mrs. Hedtke’s short story project, and to a large degree, I think my attention to language and dialogue in Hot Boy Summer stems back to feedback Mrs. Hedtke wrote in the margins of my assessment, which was to “use dialogue to show who your characters are.” In this way, a school project really did change my life. And by writing her letter for Mr. Villarreal’s English class, Flor’s project changes Mac’s, Mikey’s, and Cammy’s lives as well as her own.

Books and Resources

TeachingBooks personalizes connections to books and authors. Enjoy the following on Joe Jiménez and the books he’s created.

Listen to Joe Jiménez talking with TeachingBooks about the backstory for Hot Boy Summer. You can click the player below or experience the recording on TeachingBooks, where you can read along as you listen, and also translate the text to another language.

- Listen to Joe Jiménez’s name pronunciation

- Enjoy the Booklist’s interview with Joe Jiménez

- Discover Joe Jiménez’s page and books on TeachingBooks

- Visit Joe Jiménez on his website, X (Twitter), Instagram, and GoodReads page

Explore all of the For Teachers, By Teachers blog posts.

Special thanks to Joe Jiménez and Simon & Schuster for their support of this post. All text and images are courtesy of Joe Jiménez and Simon & Schuster and may not be used without expressed written consent.

Leave a Reply