From Teaching to Writing

TeachingBooks asks each author or illustrator to reflect on their journey from teaching to writing. Enjoy the following from Sarah-SoonLing Blackburn.

Young Learners and Tough Histories: Tips for Teachers and Writers

by Sarah-SoonLing Blackburn

The brief as I understood it was in fact brief, but it wasn’t simple. I wasn’t sure if I could thread this needle:

- Write a book that’s honest and unflinching about the real struggles and racism experienced by Chinese Americans.

- Make it enjoyable and engaging for kids!

I don’t think I could have written this book if I hadn’t been a teacher. I taught third and fourth grade, a job that requires taking big, complex ideas and making them relatable for kids, keeping them interested and curious to learn more. When we had something complicated to parse, we’d gather at the carpet and talk it through. Those classroom moments felt something like magic.

When I got stuck with my writing, I would close my eyes and imagine I was sitting back in that chair. What questions would they ask? What conversations would I encourage them to start with a shoulder buddy? How would I help transport us to a different time and place, so that we might better understand it?

The more I became reacquainted with my teacher self, the easier the process became. What struck me most was how the writing became more empathetic, and how this, in turn, made it more enjoyable to read.

In an early draft, for example, I had explained that Chinese workers built the Summit Tunnel. It was a pretty straightforward passage: who, what, where, when, how. The prose was fine. But I thought about reading this passage to my class, and I could immediately picture the eyes wandering around the room, the whispered side conversations behind hands. So, I reworked it:

“Imagine standing in front of a giant, solid mountain and being told that you have to make a hole through the center of it. You can only use hand tools and some weak explosives. You have to keep working in all kinds of weather, including blizzards, without much rest, and without a comfortable place to sleep. And you have to do all of this thousands of miles away from your family, with almost no way to contact them. This was the task in front of the Chinese railroad workers.”

Now I could imagine my students perking up. If I could keep writing in my “Ms. Blackburn” voice, maybe I could be honest and unflinching about history and keep it enjoyable for kids. Maybe I could achieve the brief after all.

As I continued writing, a few important principles from my teaching days emerged front and center and helped to guide me.

1. Kids can understand complexity and nuance more than we often give them credit for. Analogies help a lot, as do connections to their own lives.

2. Kids are exposed to and aware of pretty much all of the same things we are as adults, whether we like it or not. They are aware that injustice exists. They might not understand it, however, and they might not have language to make sense of it. Reading allows them to process their thoughts and emotions about difficult topics and offers an opportunity to have discussions with trusted adults, which can help if and when they encounter or learn about injustice in their own worlds.

3. “Exclusion” might be in the book’s title, but it was important to me that the book also include plenty of stories of acceptance and belonging. A theme I repeat over and over in the book is that anytime you see struggle and oppression you will find examples of solidarity and resistance. Emphasizing this can help readers feel empowered when they encounter injustice in their own worlds, rather than feeling hopeless.

4. Telling the stories of individuals helps kids see the humanity within the broader historical narrative. I tried to introduce a range of individuals, including some lesser-known names. One standout is Mabel Ping-Hua Lee. Even as a kid she had a strong sense of justice, and she particularly cared about the rights of both Chinese Americans and women. When she was just sixteen, she rode on horseback at the front of a march for women’s suffrage through New York City’s Greenwich Village. Her story is a great example of the power that comes from learning about injustice and resistance at the same time. I hope that it inspires young readers to know that they, too, have the power to help create positive change.

Books and Resources

TeachingBooks personalizes connections to books and authors. Enjoy the following on Sarah-SoonLing Blackburn and the books she’s created.

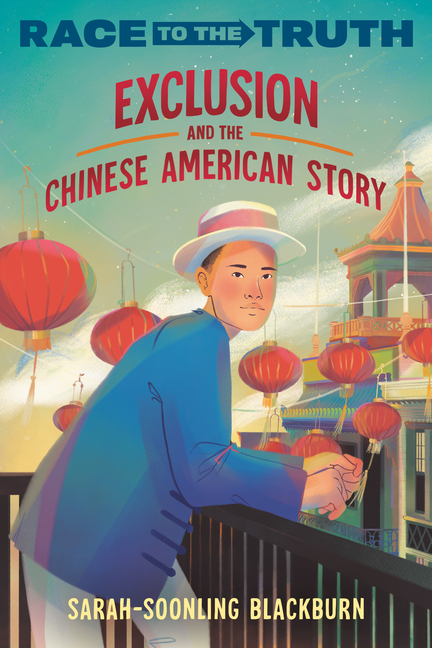

Listen to Sarah-SoonLing Blackburn talking with TeachingBooks about the backstory for writing Exclusion and the Chinese American Story (Penguin Random House, 2024). You can click the player below or experience the recording on TeachingBooks, where you can read along as you listen, and also translate the text to another language.

- Listen to Sarah-SoonLing Blackburn’s name pronunciation

- Enjoy this interview with Sarah-SoonLing Blackburn

- Discover Sarah-SoonLing Blackburn’s page and books on TeachingBooks

- Visit Sarah-SoonLing Blackburn on her website, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Goodreads page

Explore all of the For Teachers, By Teachers blog posts.

Special thanks to Sarah-SoonLing Blackburn and Penguin Random House for their support of this post. All text and images are courtesy of Sarah-SoonLing Blackburn and Penguin Random House and may not be used without expressed written consent.

Leave a Reply