Ruminations on Uncommon Punctuation

One day, the quotation marks disappeared.

I’d been drafting my middle grade novel for four years and, up to the point when the quotes vanished, the format had been ordinary. A typical book arrives, as they often do in my experience, in declarations and ruminations from the main protagonist. When I write, I begin with voice. What is my character trying to say?

In an earlier YA manuscript, (as-of-yet unpublished), the first line of the book is verbatim what the character, a 15-year-old girl, told me. She marked a line in the sand, made her preferences known. Next, her two close friends made their voices known. All three engaged in conversation, and that conversation followed regular patterns using conventional punctuation.

Throughout my life of writing, I’ve produced scripts for super-short plays, penned so-so poetry, and fumbled my way through one memorable picture book draft, written during college, whose procrastination-stunted, half-finished nature makes me shudder with shame to this day. All of these efforts followed the usual forms, bent to normal conventions. Nothing out of the ordinary here.

They say “learn the rules before you break them.” I did. My sonnets kept pentameter (except when they didn’t, as is the form’s norm). My persuasive essays included thesis statements, evidence, and punchy conclusions. I’ve pledged allegiance to the Oxford Comma, and am one of the few people I know brave enough (or perhaps ridiculous enough) to confidently use semicolons.

What then, in my second novel (first published) befell the quotation marks? What whisked them away? I wish I could tell you definitively, but the true reason is lost to time and memory. I have a few guesses:

I think rap took them. The bold, boisterousness of RUN DMC, the sable lyrics of Queen Latifah, the jazzy rumble of Digable Planets. Even though I’ve never been an attentive fan of rap and hip hop, I was raised Black on the East Coast in the 80s and 90s. Rap’s rhythms are mine and they show up in how I talk, think, dance, and write.

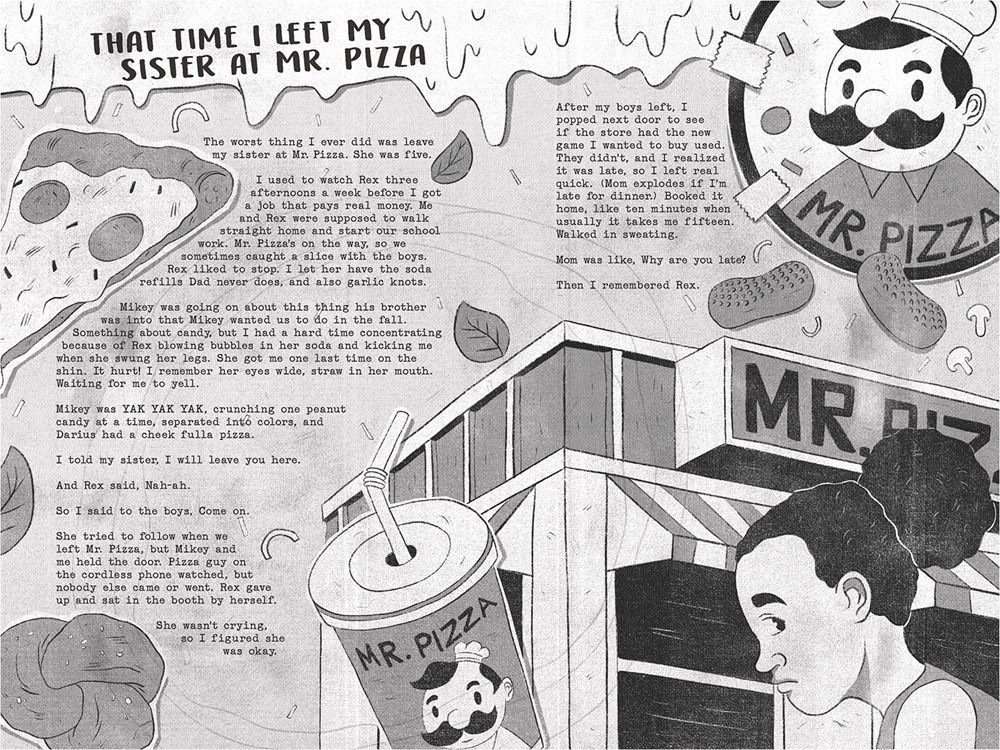

Comics challenged them. In your average Sunday newspaper “funnies” and in the pages of the floppies I purchased for $.35 from the metal circular racks in supermarkets, comics displayed dialogue in curvaceous, white speech bubbles. Each character’s statements were a break from the action, separate but no less important.

Zines broke the barrier between what was considered art, where writing fit, and how writers, artists, thinkers, and enthusiasts expressed themselves. I discovered them in college, although I’d been creating zine-like mini-books since childhood.

I can be a very deliberate, intention-directed person, but I’m not the type of artist who directs. My creations direct me: where they lead, I follow (or resist at my own peril.) When something stole the quotes from the dialogue in Confessions of a Candy Snatcher (Candlewick, 2023), I welcomed the new sense of intimacy. When I composed the first zine pages (text-only, always intending a partner-illustrator), I glowed with welcome. When Jonas and his friends spoke rapid-fire, or texted one another, script-like conversations scrolled out and I laughed as I added ellipses, brackets, and emoji.

When the “” departed, something else arrived. Something fresh, which I could not have predicted. I won’t always write without them, but in this place / space / time, I’m glad to shake loose from the norm and embrace something new.

Hear Phoebe Sinclair’s Audio Name Pronunciation.

Listen to a Meet-the-Author Recording for Confessions of a Candy Snatcher

Explore Phoebe Sinclair’s author website.

Text and images are courtesy of Phoebe Sinclair and may not be used without express written consent.

Leave a Reply