Falling in Love with Medical History—Warts and All!

As a little girl growing up in my grandmother’s house, I remember rifling through closets stuffed with oddities from bygone years: a hand-beaded purse from the 1920s with a lady’s calling card tucked inside; faded tintypes of solemn Victorian relatives posing in front of painted backdrops; a suitcase containing my grandfather’s marine uniform, along with pieces of shrapnel from 1945. Individually, these objects meant very little. Collectively, they represented my family’s past—one which was both tangible and enigmatic to a little girl whose curiosity about history would eventually reach far beyond her own genealogy.

I joke that I was a strange child, and I grew up to be an even stranger adult. When I was younger, I used to drag my grandmother from cemetery to cemetery hunting “ghosts.” Some people might think I had a fascination with death, but actually, I was fascinated with the past—and the people who lived there. Eventually, I decided to pursue a degree in medical history at the University of Oxford.

I am a firm believer that medical history is the most relatable aspect of our collective past. Everyone knows what it’s like to be sick. How was that experience different in the previous ages? What would you do, for instance, if you had a toothache in 1652? Who would you turn to for help if you broke your leg in 1830? What kinds of painkillers would have been available in 1794?

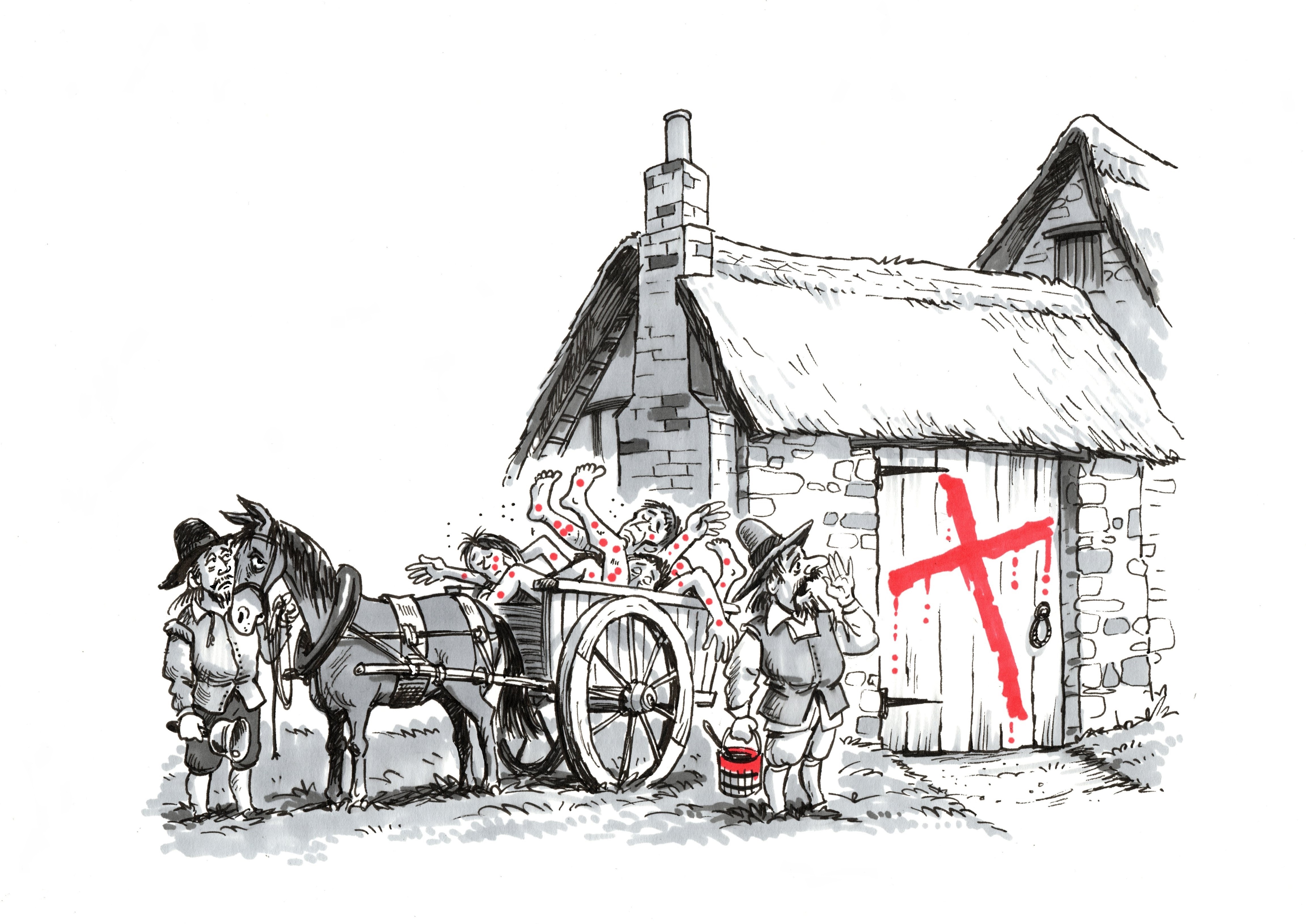

I’ve spent my entire career trying to demolish lingering romantic notions people might have about what it was like to live in the past. We are certainly lucky to live in the 21st century. It wasn’t that long ago that surgeons rarely washed their hands or their instruments, and carried with them the smell of rotting flesh which those in the profession called “Good Old Hospital Stink.” Before antibiotics or vaccinations, people died of all kinds of horrible diseases, such as smallpox, tuberculosis, and bubonic plague.

By its nature, medical history can be gruesome. For example, Victorian operating theaters were filled to the rafters with ticketed spectators, many of whom had dragged in with them the dirt and grime of everyday life. They wanted to see the life and death struggle play out before them on the center stage. There was certainly a voyeuristic aspect to it. But the Victorians were also obsessed with science and progress, and many of them bought tickets to the operating theater in order to witness the latest medical advances.

After spending years entertaining with, and educating adults about, medical history, I decided it was time to turn my attention to younger readers in the hopes of sparking a passion in them for this weird and wonderful subject.

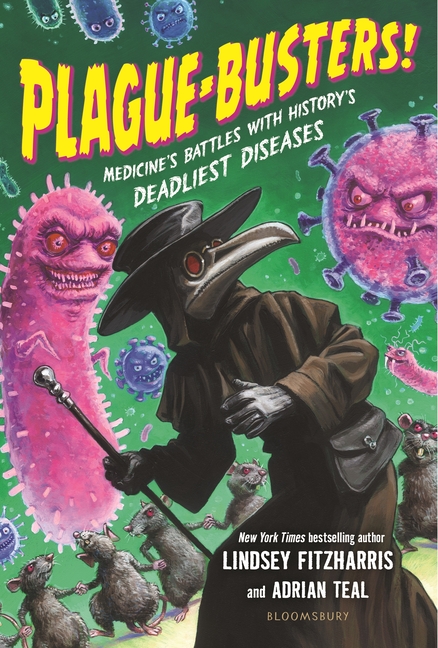

My husband, Adrian Teal, is the principal caricaturist for the British TV show “Spitting Image”. During the pandemic, he designed many of the puppets used in the show—including an anthropomorphized version of the COVID-19 virus, complete with tiny little hands. I knew then that he would be the perfect partner to help bring to life a children’s book about history’s deadliest diseases.

As a husband and wife team, Adrian and I have always found that we work very well together creatively. We are always each other’s first port of call when one of us needs a verdict on the other’s work. We wanted to collaborate on something, and since we both love delivering history in fun and engaging ways, combining our skills seemed the way to go.

Adrian and I didn’t feel that we would be doing the doctors and patients of history justice if we held back from describing what it was really like in the past. At the same time, we didn’t want to be insensitive. It’s always important to remember that these were real people. It’s a delicate balance—one that we hope we’ve gotten right in Plague-Busters (Bloomsbury, 2023)!

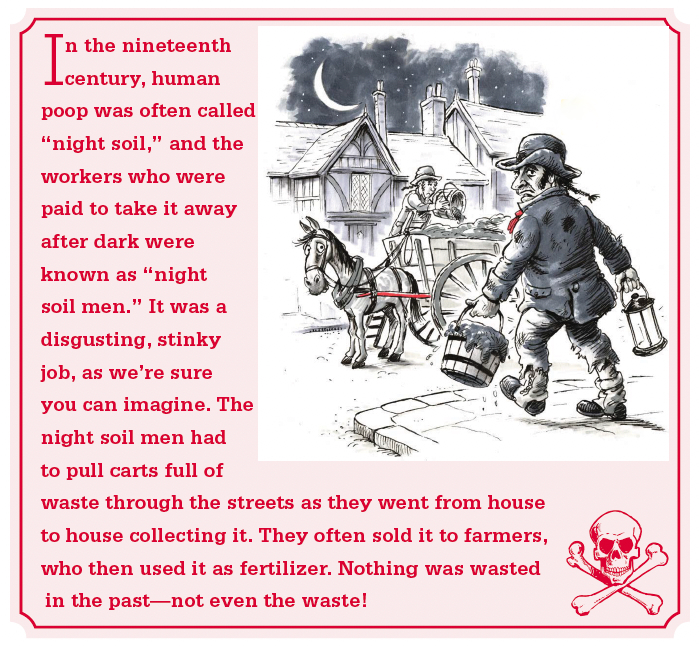

We also enjoyed bringing out the lesser-known stories about medical history. For instance, “uroscopists” were doctors who checked the color of a patient’s urine to determine if they were ill. They even had a chart called a “urine wheel,” which showed how different color pee related to a person’s state of health. In some cases, they even tasted the urine. If it was sweet, it signaled that a person had diabetes.

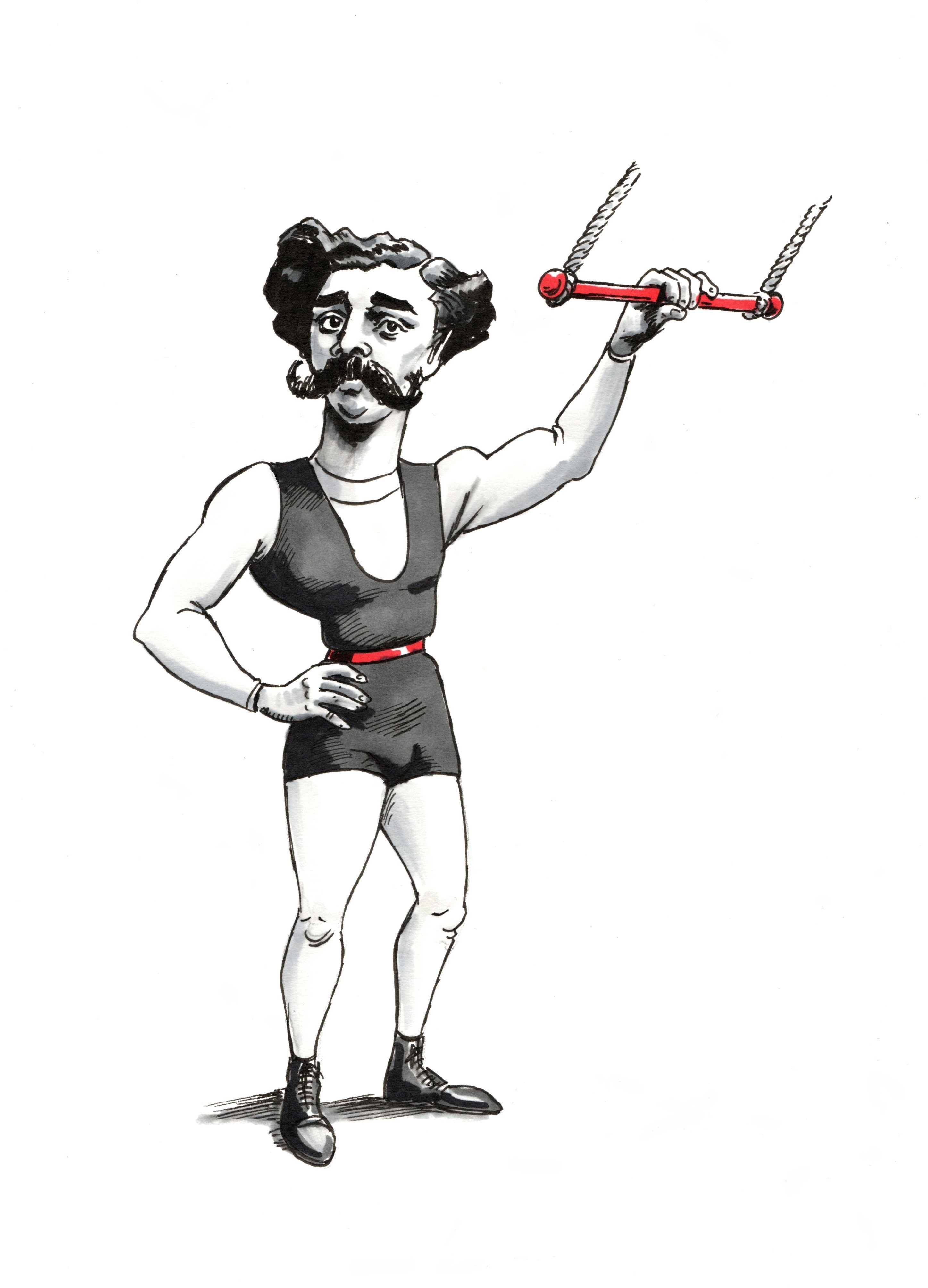

Personally, my favorite bits of the book feature the “Bills of Mortality” at the end of each chapter, which includes a list of those who died from the featured disease. Not only was it fun to research (who knew Jules Léotard, the French acrobat for whom the leotard was named, may have died of smallpox; or that Edgar Allan Poe may have died of rabies?), but it allowed Adrian to stretch his wings as a caricaturist by illustrating the famous faces.

It’s been a real privilege to have the chance to reach young minds and, hopefully, spark imaginations. Imagination is an underrated vehicle for finding a way into history. Through this book, Adrian and I hope to have inspired future generations of doctors, nurses, scientists, and, of course, medical historians.

Explore Lindsey Fitzharris’ author website.

Text and images are courtesy of Lindsey Fitzharris and may not be used without express written consent.

Leave a Reply