Visual Arts

The visual arts are a language. Just as you learn to speak, read, and write, you can also use the visual arts to express yourself and even tell a story. It doesn’t matter if you can draw; you can still use art as a language. Let me say that one more time: It doesn’t matter if you can draw. What’s most important is your interest in things like color, composition, texture, light, and shadow. An artist can mix and match these elements just as we choose the right words to make a sentence.

For instance, have you ever noticed how people say you’re feeling blue? Color can say a great deal about how we feel. I can talk about it until I’m red in the face—color has meaning. It’s just one element that can be added to what we can call a visual sentence.

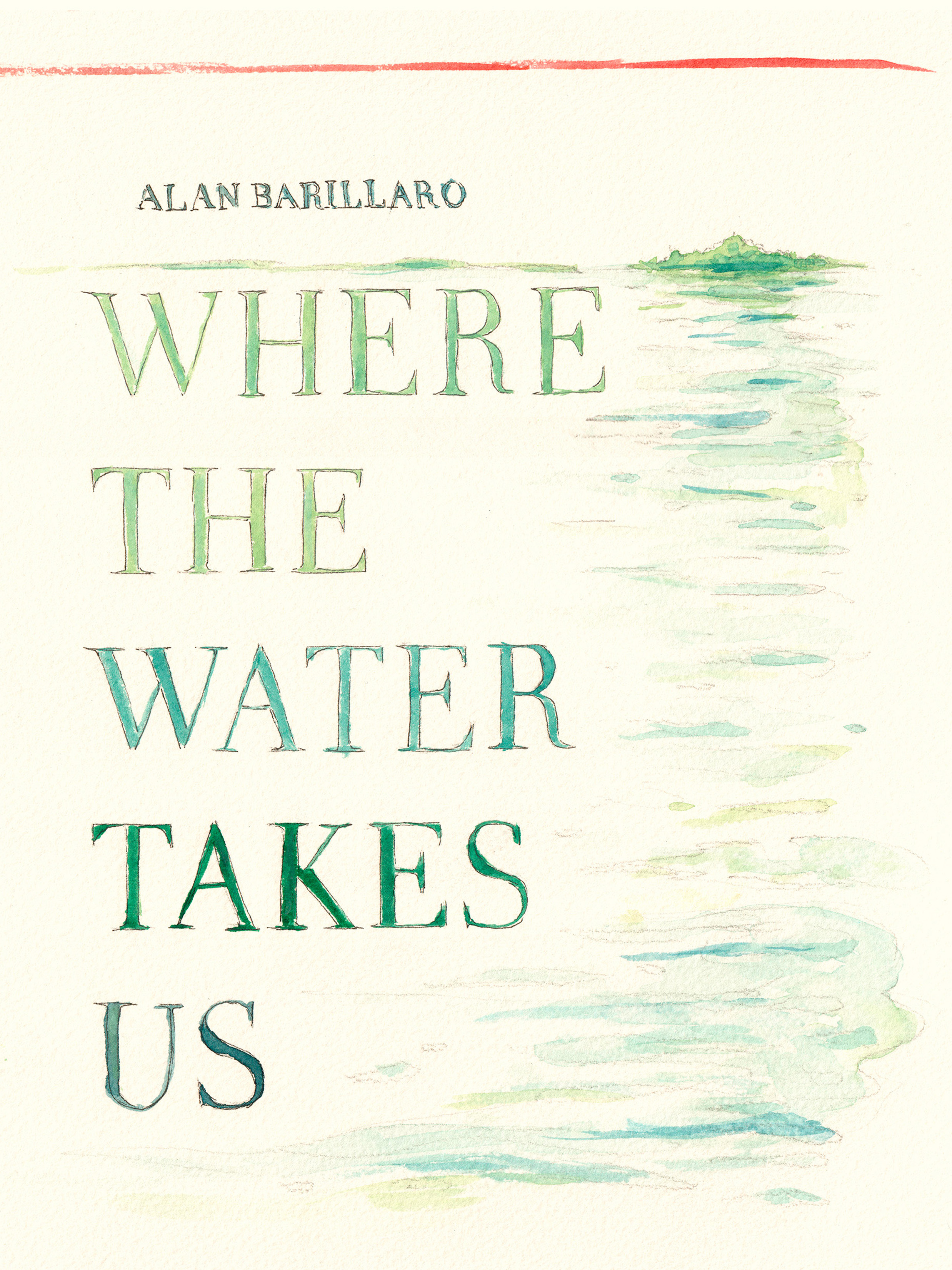

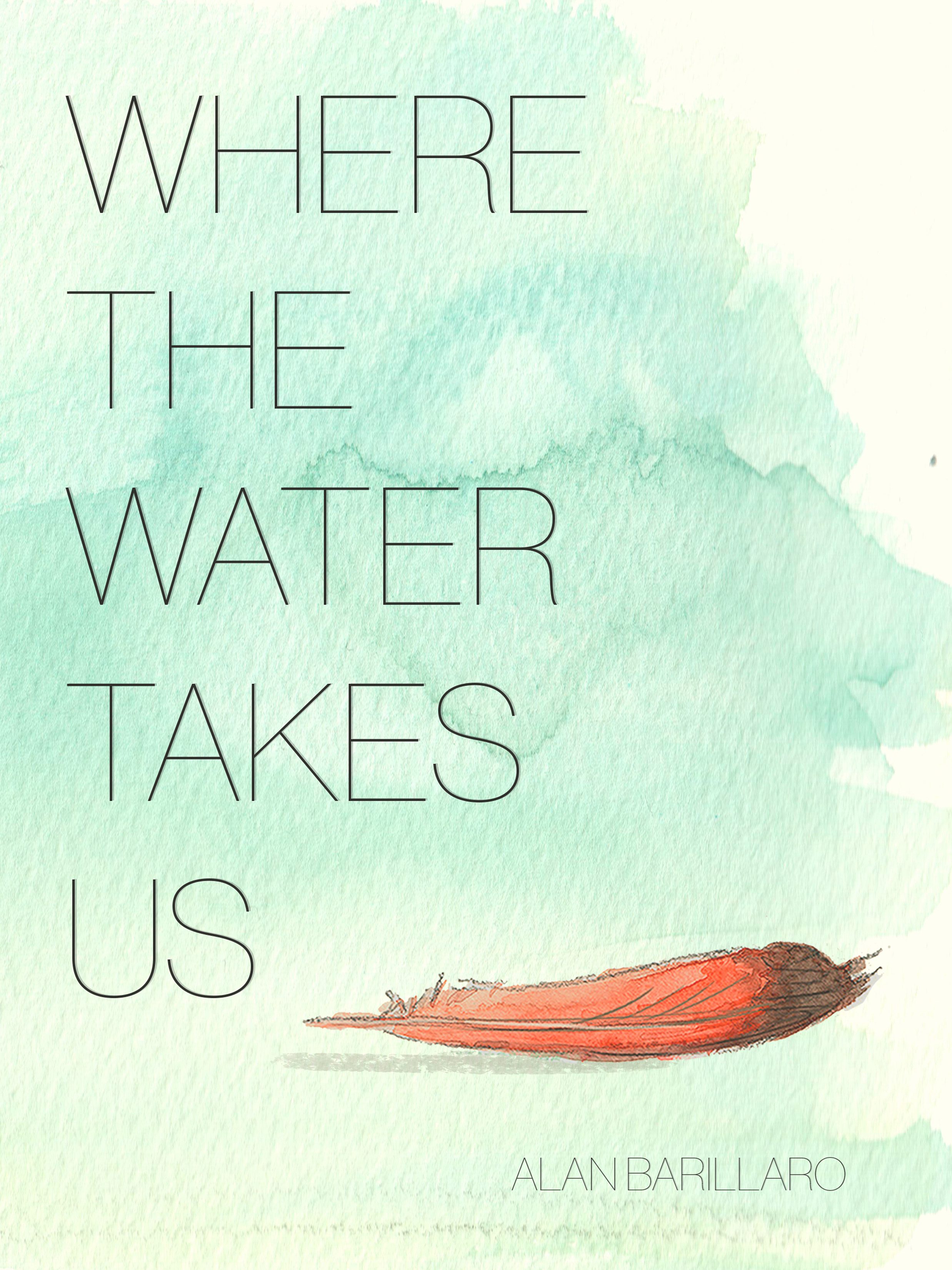

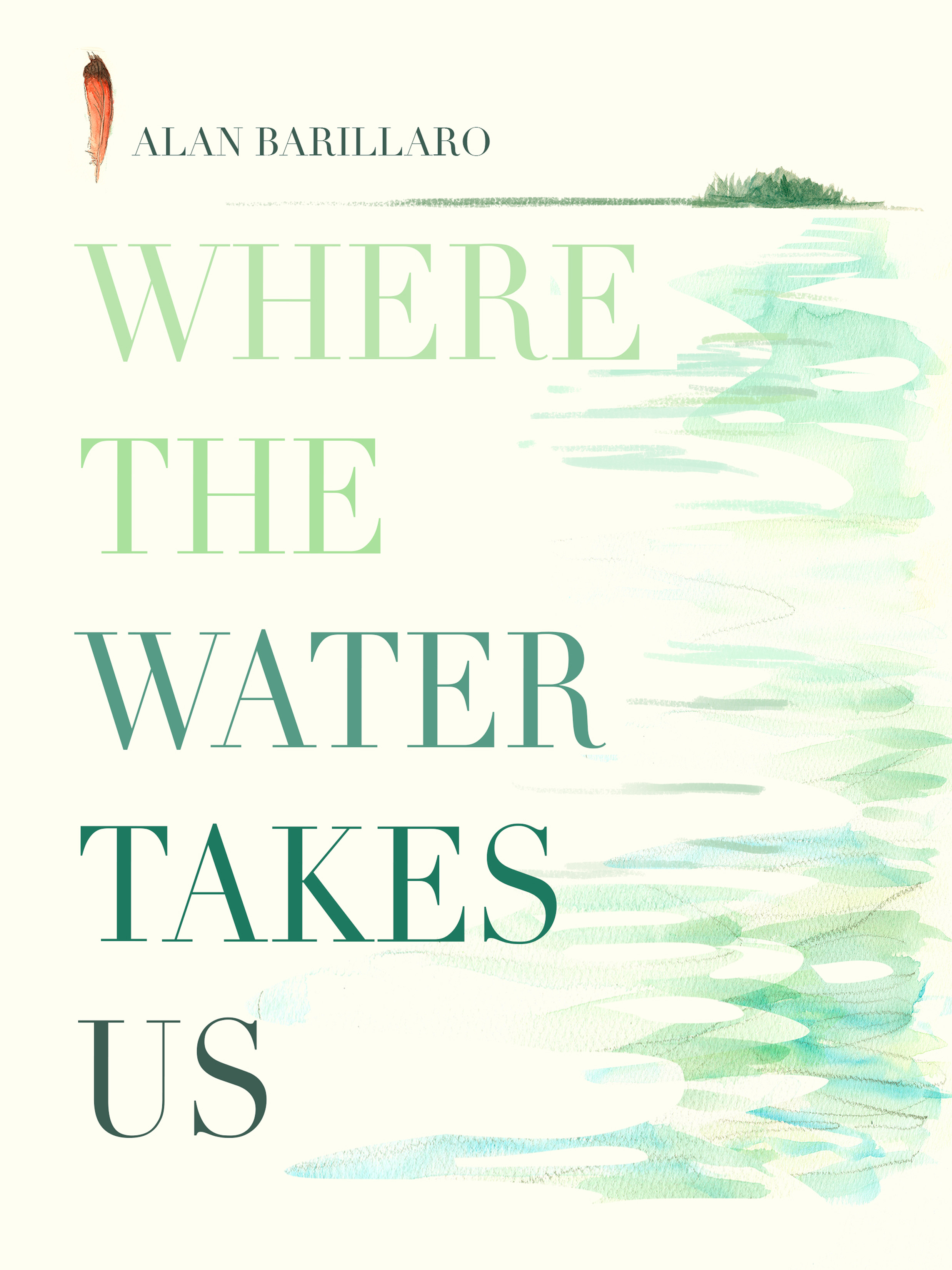

Let’s use the cover of Where the Water Takes Us as an example. How do I, as the author and illustrator, give the reader a sense of what the story is about? The truth is, my choices are endless! The hard part is deciding exactly what to say. Here are different cover sketches I tried for Where the Water Takes Us. You’ll see I’m searching for the exact visual elements to describe what I’m thinking.

In the first versions below, my visual sentence went something like this: “This is a story that takes place on the water. This feather is important to the story.” The water is green because I felt it was a more exciting color than blue.

How does the cover make you feel? I had to ask myself, What if I were walking by the bookstore? Is a cover that says “This is a story about a feather and water” the best way to describe my story? Perhaps there are a few more descriptive words I can add to my visual sentence. What if the cover transports the reader to a specific place? Let’s add a little more detail, words like lake and islands. What if there was a woodpecker flying off in the distance and the sky was stormy, suggesting there is trouble on the horizon? Does that get us closer to the story inside? For weeks I painted countless stormy lakes and woodpeckers. It was the right direction, but something was wrong. To me, the visual sentence I kept creating said something like, “This is a story about a woodpecker that lives on a lake.” Is that really the story of Where the Water Takes Us? I felt it was getting closer, but still the cover was not quite right.

Luckily, when you make a book, you get to work with all sorts of smart people who help you along. The conversation quickly became, “Who’s this story really about?” “Well, it’s eleven-year-old Ava’s story.” “What about including Ava on the cover? What if the visual sentence read, ‘This is a story about a young girl on a lake’?” I went back to some of my first sketches of Ava. (The black-and-white sketch is one of my very first drawings of Ava.)

So I set out to try to include Ava. Let’s skip over the dozens and dozens of versions where I was trying to get this visual sentence just right. Below is the final version. Hopefully, the visual sentence I came up with is accurate to the story inside without giving too much away. (I don’t like covers that give the whole story away!)

I hope all this searching of mine shows you just how much art is always about communication. Whether you can draw or not, or choose to use photography or typography, there are countless techniques and mediums available that allow you to express yourself. Which medium you choose and what you ultimately choose to say with that medium is what the power of language is all about. It’s unique to you!

Discussion Questions and Exercises

- What additional choices do you think were made on the cover that give clues to the reader about what type of book this might be? Why is watercolor paint used as a medium? Are there other choices, from composition to the style of the text, that give you a feeling about the book? Which visual element did you notice first?

- What if we switched the size and placement of Ava with the woodpecker? What would emphasizing the woodpecker say about the story? How does composition change the visual sentence?

- Imagine you need to create a new cover for your favorite book. What’s the most important thing you want to say about the story inside? Can you put that idea down into words, then try to describe those words visually? For instance, “Hey you, walking by this book! This book is completely silly! You’re going to laugh so hard!” What colors would you use to say that? How would you design the title and the text? Remember, plenty of covers are abstract images, but still leave us with a powerful feeling about what the story inside might be like. Sketch some rough ideas for your new cover. Come up with as many ideas as you can and see what they say about your story. Pick the one you like most and show it to others to see what their interpretation of your cover is. WARNING: By the end of this exercise, you will have visually communicated something to someone else! Guess what that means? It means, whether you can draw or not, you’re an artist! Yikes!

Science

In Where the Water Takes Us, eleven-year-old Ava finds two abandoned eggs from an American robin. With the help of her grandmother, she raises the two birds. It doesn’t take long for Ava to find out just how difficult it is to keep baby robins healthy and safe. (It is so difficult to take care of baby birds that it must be done by professionals, like your local wildlife rescue . . . or a grandmother like Ava’s, who is a knowledgeable volunteer for an animal shelter.)

As an author, I had plenty of homework to do in order to write just how Ava would take care of two baby birds. Science textbooks were involved! I read up on how to hand-rear birds and checked in with aviculturist experts who had firsthand experience raising birds.

One of the things I learned was that the way robins grow up is not so different from the way we grow up. There’s of course a baby stage, and the screaming toddler stage, and the rebellious teenager stage—it all just happens in days instead of years. But how often do we see these stages in nature? A robin is typically represented with its colorful red breast (though to my eye it’s more orange than red). When we see an image of a robin, we’re usually seeing the most colorful representation, which is the adult male robin. What about female robins and all the other stages we mentioned?

There are two birds in our story, Hazel and Red. As fledglings, their brown downy feathers help them camouflage into their surroundings, especially before they can safely fly away from danger. Below is a simplified chart where I noted some differences between male and female robins from birth to adulthood. There are other stages, like nestling and juvenile, but this chart shows some of the major developmental differences from one stage to another. Creating or studying charts like these will help you identify the birds in your neighborhood. You’ll learn who’s living right next door to you and how big their family might be! Not only that, but identifying birds tells us a great deal about the natural world around us and the health of our neighborhood wildlife.

Text and images are courtesy of Alan Barillaro and may not be used without express written consent.

Leave a Reply