From Teaching to Writing

TeachingBooks asks each author or illustrator to reflect on their journey from teaching to writing. Enjoy the following from Camilla De La Bedoyere.

On Teaching and Writing

by Camilla De La Bedoyere

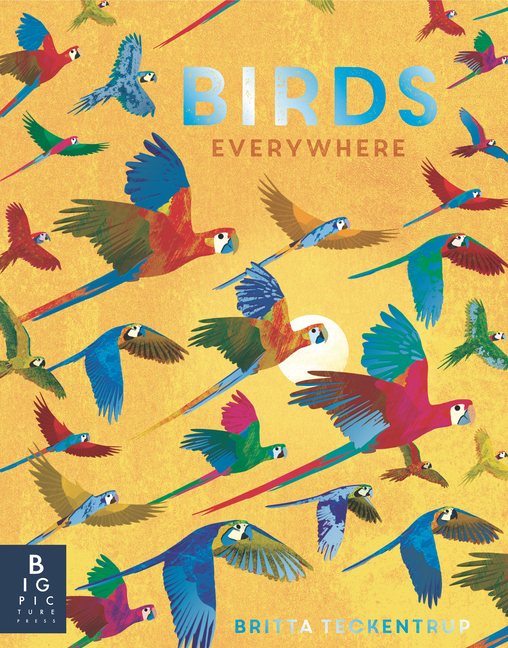

I love storybooks—we all do. But I’m waving the flag for the less glamorous world of nonfiction books.

I’ve been asked, on more than one occasion, if I have plans to write a “proper book” at some point in my career. It’s a strange question to ask someone whose writing career has spanned nearly thirty years and who has more than two hundred and fifty titles in print around the world. Further inquiry reveals that these “proper” books are fictional books for children or novels for adults. However, I mostly write children’s nonfiction, usually based on science topics and the natural world in particular. Like I said, not particularly glamorous.

But put a great book about sharks in a child’s hands and you’ll see how quickly and easily they become entranced by the photos or illustrations, how fascinated they are by amazing facts, and how many questions begin popping into their active minds. Their interest and imaginations piqued, you have opened the door to a wealth of exploration and knowledge and the beginning of a child’s lifelong journey to try to understand the world around them.

Nonfiction books are also extremely useful tools for helping children learn to become skilled readers. I know this because, in addition to my writing career, I teach literacy skills to students part-time. The two strands to my career blend perfectly, keeping me in touch with the interests and reading skills of young people and helping me to continually develop my own writing.

When introducing new vocabulary, you need to keep your sentences simple so the language flows easily, carrying your young reader along with you.

Any writer will tell you that writing for children is much harder than it looks, and writing science-based books brings considerable challenges. When introducing new vocabulary, you need to keep your sentences simple so the language flows easily, carrying your young reader along with you. Now that you know that rule, try to write explanations of the concept of density, the aerodynamics of bird flight, how animals evolve, bioluminescence in deep-sea fish, or global climate change. Bear in mind that your reader is just seven years old, so vocabulary must be accessible, the grammar and syntax simple . . . oh, and yes, your word count for each of those themes is thirty-five words. Good luck!

You also have the design and illustrations to consider. When you are first writing your text, there will be no design or artwork in place, so you are imagining what each page might look like, what artwork will help your explanations, and how the design will help guide the reader around a topic. Once the layouts of the book have been sketched out, you may find you have to amend your text to suit what the designer and editor have achieved. It might even require a complete rewrite.

All of this is tricky, but it is a great deal easier when you have experience with how young readers tackle books, and that’s where teaching comes in handy. I work with youngsters between the ages of eleven and fourteen who struggle with reading. Their reading skills are typically those of eight- and nine-year-olds, but some of them find it difficult to read even the most basic texts. A few of my students are learning English as an additional language, but most have learning difficulties, especially delays to language development, and most of them have a diagnosis of dyslexia, ASD or ADHD, or memory, cognitive, or processing difficulties.

My teaching experience means that, when I write, I am aware of how a young reader will tackle the text. I think about the phonics of tricky words and I aim to repeat certain phonic patterns, such as -igh or -tion, if I can so an emerging reader can practice them. Editors sometimes want to remove repeated words, as it might be considered poor style, but as teachers we know that children benefit from having new words repeated several times. Occasionally editors want to swap a word I’ve carefully chosen for an alternative, but I know that while my word may be three syllables long, it is phonetically easy to decode, so it’s a win for me, the child, and their teacher.

For all students, nonfiction books can be beneficial in developing reading skills, but I strongly recommend them for struggling readers, who are often put off by prose-based books. Informational books usually feature plenty of pictures, colorful designs, and bite-size chunks of text, even when aimed at older readers. New words are explained, either within the text or in a glossary. All of this helps readers stay focused, feeds their self-esteem as they gain knowledge, and allows them to read in short spurts, which is helpful for students with dyslexia.

Lessons often go off on a tangent and we’ll stop to look up information and pictures to dive further into a topic to help us understand the story we are reading on a deeper level.

Nonfiction books can also provide essential contextual information for fiction books that children are enjoying. My bookshelves at school are lined with many informational titles that we regularly dip into, such as atlases, encyclopedias, biographies, and books on space, rain forests, climate, and history. Lessons often go off on a tangent and we’ll stop to look up information and pictures to dive further into a topic to help us understand the story we are reading on a deeper level. This activity provides plenty of opportunity to discuss the story we are sharing and what we are learning, which helps children further develop their communication skills.

Finally, and just as importantly, the reading and analysis of nonfiction books in the classroom now plays a crucial role in tackling the plethora of misinformation in our world. With phones, tablets, and computers playing such a dominant part in children’s lives, we must teach young people how to choose trustworthy sources of information, how to fact-check, and how to weigh the validity of sources. These critical thinking skills, along with improved reading comprehension and general knowledge, will help turn our young people into adults who have the tools they need to make sense of an ever-changing world and play active roles in shaping their own futures.

Books and Resources

TeachingBooks personalizes connections to books and authors. Enjoy the following on Camilla De La Beyodere and the books she’s created.

- Discover Camilla De La Beyodere’s page and books on TeachingBooks

- Visit Camilla De La Beyodere on her website, GoodReads, and LinkedIn

Explore all of the For Teachers, By Teachers blog posts.

Special thanks to Camilla De La Beyodere and Big Picture Press for their support of this post. All text and images are courtesy of Camilla De La Beyodere and Big Picture Press, and may not be used without expressed written consent.

Leave a Reply