From Teaching to Writing

TeachingBooks asks each author or illustrator to reflect on their journey from teaching to writing. Enjoy the following from Lauren Kate.

Not Knowing

by Lauren Kate

I teach Advanced Fiction at an online middle school called Astra Nova. Students enter the class with stories they’ve already written and want to expand into something longer. On the first day, I ask students what they don’t know about their stories.

Confused silence ensues. Which tells me the class is going to be successful.

When writers begin a story, they usually know something about their main character. Or they can picture a fantastic setting. They might be clear on an inciting incident, or an injustice they want to shine a light on. It’s natural to start with what you know, because the alternative—considering all you simply can’t know—feels like falling into an abyss.

My job is teaching students how to fall in love with that abyss.

E. L. Doctorow says, “Writing a novel is like driving a car at night. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.” That’s great advice if you want to de-mystify the writing process, but writers are a mysterious bunch. We’re interested in the darkness at the edge of those lights. That’s why I encourage my students to be curious about what they don’t know. What they might never know.

We do a meditative writing exercise together. I learned it third-hand from the poet Farnoosh Fathi. Everyone chooses an object we can see from our desks, and then, with our attention softened, we look at the object for five minutes, thinking the phrase: “I do not understand this object yet.” Whenever our thoughts wander, we bring our focus back by reminding ourselves that we do not understand this water bottle or lamp shade or tissue box…yet. We linger in the realm of the unknown, the un-understood, and eventually something shifts.

“Whatever we learn requires patience—or, at least, it requires abiding impatience.”

Then, for the next five minutes, we write about the experience of not understanding our object. We write about how it feels to confront what we don’t know. And afterwards, when we read our reflections to one another, I’m always surprised by our wisdom. Sometimes what flows in arrives from the subconscious. Sometimes it’s a strange sensory insight. Whatever we learn requires patience—or, at least, it requires abiding impatience. You have to be willing to be wrong about your object. You have to be willing to be wrong about the story you want to tell.

Creative Writing is the rare academic discipline where you indulge and explore your ignorance. You shouldn’t do that on an algebra exam, but it’s essential for making fiction.

I was certainly ignorant of what my next novel would be in March, 2020. My children’s school had shut down because of the pandemic, and Zoom classes were a thing of the future. So every morning, my six-year-old son and seven-year-old daughter joined me on my previously solitary hikes, when I was used to intense quiet for working through my story problems.

This was an era when the world became unknowable in new ways: How long would everything be closed? How large a toll would the virus take? When would my kids see their friends or grandparents? None of us understood this object yet.

Each day I watched my kids disappear into the woods along the trail, and I thought back to my own childhood disappearances into trees. The seed of a story—about four children who find something important in the woods behind their houses—sprouted in my mind.

For weeks I walked around with this idea, wondering what those four kids find. I couldn’t see it. So I focused on what my headlights illuminated: who the characters were, where the story would be set. I waited in the abyss, abiding my impatience.

One night that spring my daughter lost a tooth. And as she placed it under her pillow, she asked me if I thought fairies ever wondered if kids were real, the way children wonder about fairies. I said I didn’t know, because I didn’t.

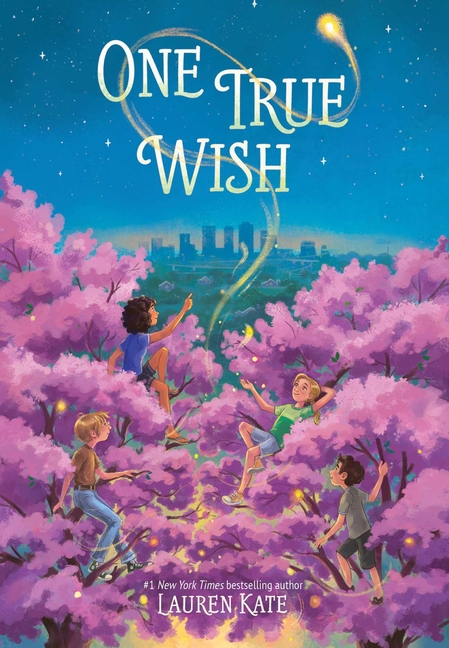

The next morning, when my kids vanished on our hike, a skeptical fairy who doesn’t believe in children asked me to write her into One True Wish. I was happy to oblige.

A school year only lasts nine months. Sometimes that’s enough time for ignorance to blossom in my students’ writing. But if I can help them hold onto their impatience, their unknowingness, no matter the form of the abyss, I’ll have done my job as a teacher.

Books and Resources

TeachingBooks personalizes connections to books and authors. Enjoy the following on Lauren Kate and the books she’s created.

Listen to Lauren Kate talking with TeachingBooks about the backstory for writing One True Wish. You can click the player below or experience the recording on TeachingBooks, where you can read along as you listen, and also translate the text to another language.

- Hear Lauren Kate talk about how to say her name

- Discover Lauren Kate’s page and books on TeachingBooks

- Visit Lauren Kate on her website, Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, and GoodReads.

Explore all of the For Teachers, By Teachers blog posts.

Special thanks to Lauren Kate and Simon & Schuster for their support of this post. All text and images are courtesy of Lauren Kate and Simon & Schuster, and may not be used without expressed written consent.

Leave a Reply