From Teaching to Writing

TeachingBooks asks each author or illustrator to reflect on their journey from teaching to writing. Enjoy the following from Kellye Crocker.

When I start a session as a visiting creative writing teacher, I tell my students I only have two rules: Respect and Try.

Respect is straight-forward. We’re going to treat everyone as if they’re valuable human beings, because they are. Students have no trouble providing examples of what this looks and feels like.

Try is trickier. They talk about working hard. Giving their all. Trying their best. “Trying is for losers,” one fifth-grader told me. That approach might be necessary for Jedi training, I tell them, but for our time together, I want you to not try your best. Whatever we’re writing that day—sensory stories, dialogue subtext, color poems—I simply want them to give it a go. Mess around with words. See what happens. No biggie.

When writers feel relaxed, when they’re not required to produce something brilliant on the spot, when they have space to breathe, they can more easily explore their ideas, notice and follow odd impulses, and play in their work. They can create something original. Have fun, even.

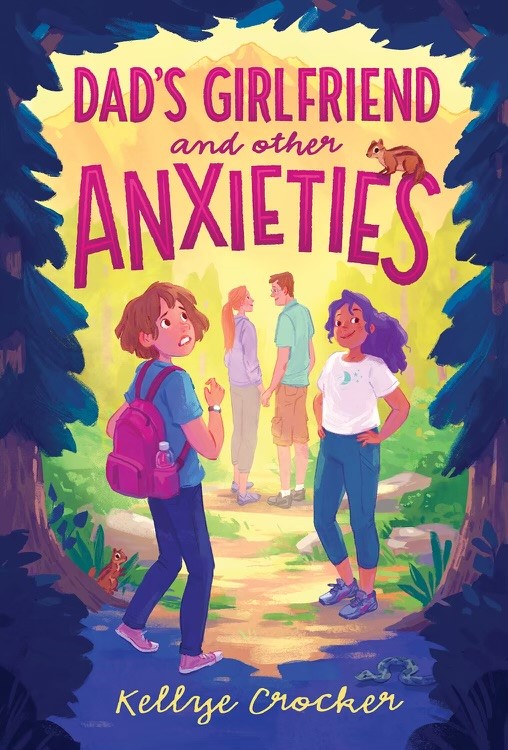

This attitude carried me through writing my debut middle grade novel, Dad’s Girlfriend and Other Anxieties, which will be published in November.

In teaching, this approach works well for skilled writers—especially young people who love writing but can be derailed by perfectionism—and for those who claim to hate writing. I have to admit, I’m especially fond of the haters.

I’ve taught creative writing through a large literary nonprofit in Denver to elementary, middle school, and high school students, in public and private-school classrooms, at a children’s hospital, public housing community centers, and public and school libraries. Some were one-time gigs, such as the conference in Colorado Springs for gifted kids where my high-school-age students were in college, with one 16-year-old finishing her master’s. Most, though, have been weekly sessions over a month or more, which I appreciate so I can get to know the students better.

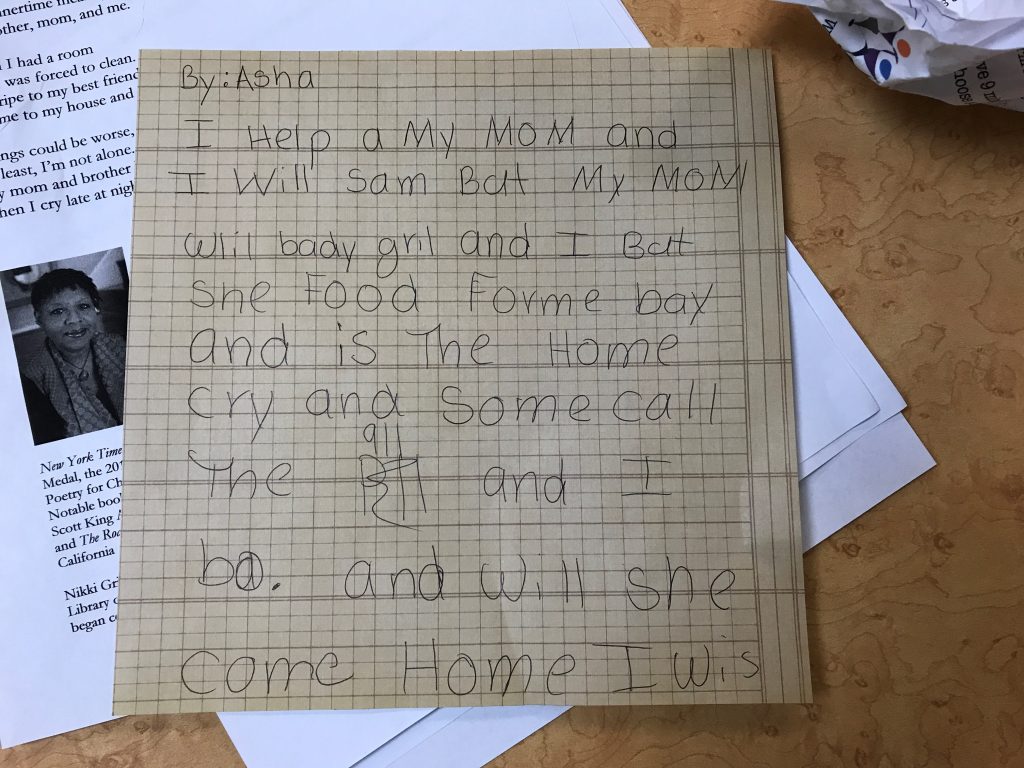

No matter where I’ve taught, I’ve noticed a pattern among the Writing Haters: They’re bad spellers. They assume that makes them bad writers, too. And maybe dumb. This thinking breaks my heart and, of course, can have devastating, lifelong consequences. But it’s also wrong.

Students are surprised to learn I struggle with spelling, too. (They see I’m not joking when I write on the board and, inevitably, encounter a word I can’t spell.) Despite this, I’ve worked as a professional writer my entire adult life, as a newspaper and magazine journalist and now as a novelist.

Because here’s the thing: Writing isn’t about spelling!

It’s about communicating.

Spelling and grammar are important. Of course. Full stop. But only because they enable communication.

I know, I know. Easy for me to say, right? No one’s holding me accountable for these students’ standardized test scores.

Meanwhile, classroom teachers are racing to do more with less. All. The. Time. You’re hitting those curriculum benchmarks while serving students who lost their emotional and academic footing during the pandemic. It’s all happening in a dumpster fire of a political climate, where teachers and librarians are threatened for doing their jobs.

Because of this, writing is more important than ever. I tell my students about scientific research that found writing makes you think differently, boosts your creativity, and helps you express yourself. Those are skills students need no matter what they dream of doing with their lives. Yet, a friend who left teaching this year told me her school curriculum had held no space for students to explore their creativity.

This is the time to double-down on creativity. (See the “creativity crisis” work of K.H. Kim, a College of William & Mary researcher and education professor.)

As a journalist who often interviewed young people—and, later, as a teacher—I haven’t met a student who didn’t have strong opinions and preferences about something, who wasn’t brimming with ideas, stories, and imagination. (For a variety of reasons, some may need extra support to tap into them.)

I want my students to express themselves with writing, to have the courage to bring their full weird and wonderful selves to the page, to say what only they can. That’s more than enough.

We’ll get to spelling and grammar later, when we discuss how drafting (including activities such as prewriting and planning) requires different skills and uses different parts of the brain than revising and editing.

I never require students to share their in-class writing, but many volunteer, including the shy and/or reluctant writers. Their stories make me, and their peers laugh and hurt, ponder and marvel. Each is a writer, even those unlikely to win the spelling bee.

Margaret Atwood said, “A word after a word after a word is power.” When young people realize they’re good writers—as well as smart and creative thinkers—and that—whoa! writing can be fun? —and that their writing can make people laugh or question or argue, they step more fully into themselves and their power.

Here’s a small moment that had a profound effect on me. A student announced he’d finished writing his story, and I went to his table to read it. He was enrolled in a community summer program for economically disadvantaged kiddos who needed academic help. My co-teacher and I had worked with the group for several weeks; they didn’t have a choice about joining our class. Even though this guy self-identified as a Writing Hater, he was generally good-natured and always tried. When we asked who wanted to read their writing, his hand shot up.

I no longer remember what he wrote that day. But it was good, and I told him so.

“Do you realize how smart you are?” I asked.

He nodded, distracted, already rising. It was time for recess. Then my words seemed to sink in. He paused, turned back, his eyes meeting mine. In an instant I knew he understood. I meant it. He was good at this writing thing. And smart. And he knew it, too.

It’s shocking how often I forget all of this when it comes to my own writing. The students I work with inspire me with their good humor and vulnerability. Teaching creative writing keeps me connected to these truths: Stories are built in layers, not all at once. A messy draft is something to celebrate. Writing is healing and an escape. Sharing our stories is powerful. We read and write to connect—with others and ourselves. When it’s hard, all we have to do is try.

Books and Resources

TeachingBooks personalizes connections to books and authors. Enjoy the following on Kellye Crocker and the books she’s created.

Listen to Kellye Crocker talking with TeachingBooks about the backstory for writing Dad’s Girlfriend and Other Anxieties. You can click the player below or experience the recording on TeachingBooks, where you can read along as you listen, and also translate the text to another language.

- Listen to Kellye Crocker talk about her name

- Explore the Discussion Guide for Dad’s Girlfriend and Other Anxieties

- Discover Kellye Crocker’s page and books on TeachingBooks

- Visit Kellye Crocker on her website, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, and GoodReads.

Explore all of the For Teachers, By Teachers blog posts.

Special thanks to Kellye Crocker and Albert Whitman & Company for their support of this post. All text and images are courtesy of Kellye Crocker and Albert Whitman & Company, and may not be used without expressed written consent.

Leave a Reply