Frustration is the Point

by Kerry O’Malley Cerra

I think most writers have been told at some point in their careers to “Write what you know.” I suppose it’s sound advice. Or at the very least, a good jumping-off point. But for me, that advice meant potentially writing a character with hearing loss, and when I started down this career path, I was nowhere near the point in my life where I talked about my hearing loss publicly. So I wrote stories with fully-abled characters instead.

As my hearing deteriorated, it became harder to brush off my disability. I could no longer hide from the truth. I’d worn hearing aids for years, but those were beginning to fail me as I approached total deafness. Around 2014, as the #weneeddiversebooks movement gained traction, people in publishing were taking note of the need for books with all types of representation, especially in children’s literature. I watched in admiration as other authors opened up about the challenges they faced—some big, some small. All of them were incredibly brave.

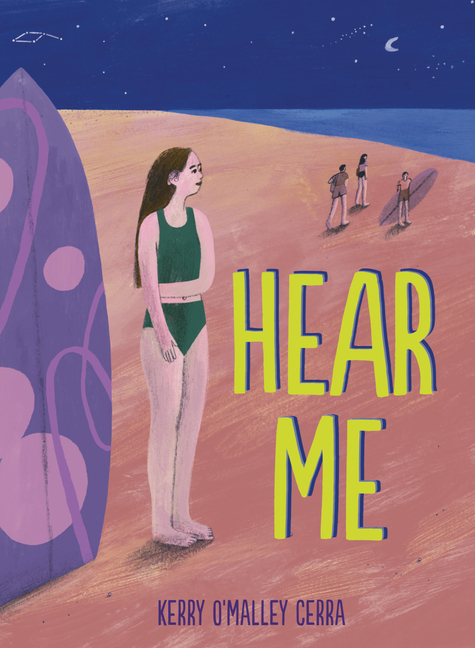

I still didn’t intentionally set out to write a story like Hear Me (Lerner, 2022), and yet one day the whole first chapter came to me word for word. That’s never happened. I knew that opening—Rayne sitting in the audiology booth for a hearing test—was powerful. I also knew that at sixteen years old, when I was first diagnosed, if I’d read a book with someone like me, I likely would have been less ashamed of my circumstance. So I ran that chapter by my critique group, and they were taken aback by the rawness of it. They’d known me for years, and they knew I had severe hearing loss, but they’d never fully understood my situation until that moment. And as far as Hear Me goes, there was no turning back at that point.

Authors have many choices to make when crafting books. One of those critical choices is point of view. I’ve always written in first person present tense (I know not everyone is a fan, but it’s my favorite). With Hear Me, it felt especially important to write in first person—to write an authentic hard-of-hearing character and let the reader experience the challenges people like Rayne face.

I used *** in sentences to represent what Rayne can’t hear in everyday conversations. My goal with the asterisks was to show how little Rayne hears. How hard she has to work—using context cues, lip reading, inferencing, and more—to fill in gaps and try to make sense of what’s being said. I also hoped to convey how physically exhausting this is.

I was actually judicious in my use of asterisks, to avoid making the dialogue totally indecipherable to the reader. Rayne is a candidate for cochlear implants, so her hearing is worse than I present on the page. But it’s important to note that Rayne’s brain does think it’s actually hearing the words she’s puzzling together, and therefore the dialogue in this book represents her understanding rather than what she actually hears.

One early reader suggested changing from asterisks to light gray words after Chapter Three. The reader noted that they understood why I did this, but they were frustrated and felt other readers would give up on the book. So I was asked to consult my publisher about changing the asterisks to lightly shaded words instead. This gave me great pause. Of course, I hated the thought of readers giving up on my story. But I wanted readers to get a firsthand sense of Rayne’s everyday challenges. The more I contemplated the request, the sadder I got. An able-bodied reader was asking me, a disabled writer, to enable them more. I politely declined, and I stand by the choices I made in crafting Rayne’s character and executing the delivery of her story. It is frustrating. I get that. But it’s also the point.

While I know that many readers won’t identify with Rayne’s hearing loss specifically, I believe most will connect on some level with her longing to be heard. Her need to be taken seriously. Her desperation to know that her opinion—especially when it comes to her own body—should be valued. That truth, Rayne’s truth, is universal.

Text and images are courtesy of Kerry O’Malley Cerra and may not be used without express written consent.

I can’t wait to read this book! My WIP has a male character who is keeping a secret from his best friend and his team mates. He is denies the importance of taking insulin for his newly diagnosed Type 1 diabetes. My difficulty is writing 13-year-old makes! Looking forward to your tween book which I know will be a mentor text for me.

Thank you for your bravery!

Kerry,

I have been reading Hear Me and I am captivated. I am so proud to know you and have worked

with you as a fellow school librarian/media specialist. Your gift of story is one to be shared and it is great to

see you here on this incredible platform, Teaching Books reaching and educating many more diverse readers.