From Teaching to Writing

TeachingBooks asks each author or illustrator to reflect on their journey from teaching to writing. Enjoy the following from Bridget Farr.

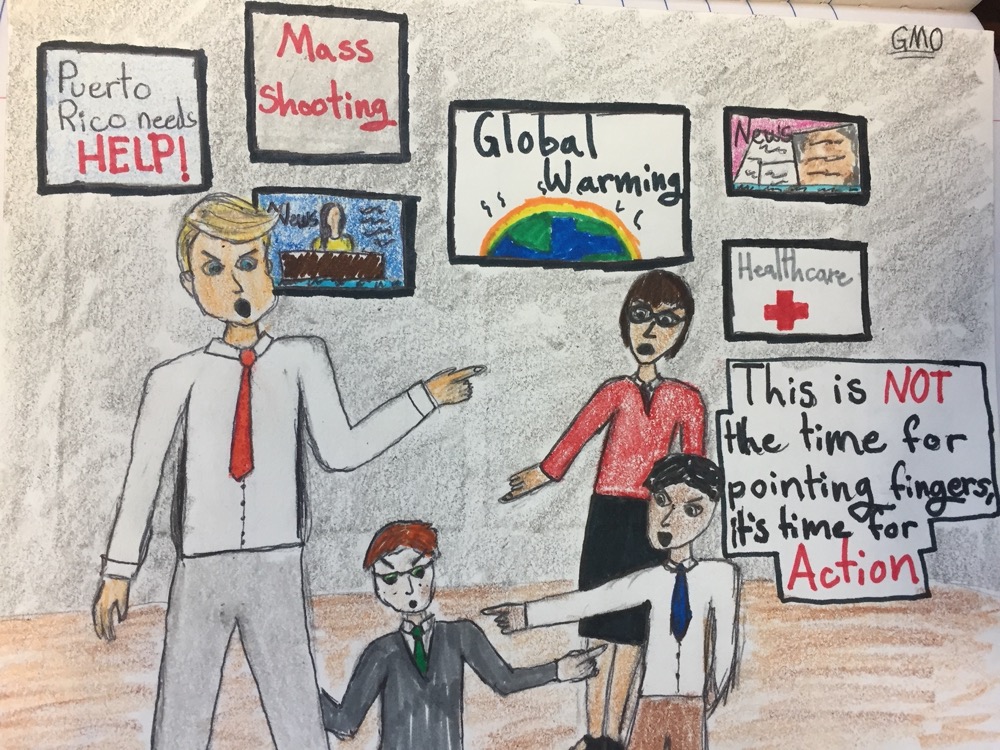

I taught a lesson on peaceful protest thirty minutes before the students on my campus led a school-wide walkout. I’d spent the class period showing photos from sit-ins and marches, preparing the sixth graders for our upcoming Living Newspaper projects where they’d turn human rights issues into poetry-based protest plays. As students lined up for lunch, I stood gape-mouthed as one Latinx boy went student by student demanding, “Are you going?”

“Going to what?” I asked though I had a sense. The whole school had been humming since rumors spread that a teacher told an immigrant student to go back to Mexico. While the exact words were uncertain, the impact was clear.

“I can’t tell you.”

“The whole point of a protest is to get people to change their actions. How can they do that if they don’t know what you want?”

He shook his head. “If I tell you, you’ll try and stop us.”

The lunch bell was set to ring but I rushed to the front of the line, pulling my door closed. I don’t remember my exact words—just the pounding of my heart—as I told them that I believed in the power of protest, it’s why I was teaching them this unit, but before they chose to speak out, they had to have all the facts. Research, knowledge, a verified reason to speak up. As a teacher in the building, even I lacked details.

The bell rang. They waited for me to open the door.

“I know what happened, Ms. Farr,” he said, more confident than I was in sixth grade. “I’m going.”

I stepped aside.

Soon came the scariest moments in my teaching career. I sat in my classroom with several students in my advisory as shouts and bangs rang in the hallway outside. Together, we sat in a circle as students shared their fears, their concerns, their annoyance at their peers. When the volume outside got too loud, I ran to the door to make sure there were enough adults to supervise.

Despite my planning, I hadn’t considered the deeper questions around activism—who should be leading the movement and who is there to support?

Eventually, the students returned to their classrooms, and we navigated the last few hours of the day. The next morning, antifa protestors handed out pamphlets during arrival and a news truck parked in the faculty lot. Angry parents showed up at a school town hall, and teachers sat in restorative circles during our planning. I was exhausted and overwhelmed as the complexity of the situation began to unravel.

Mostly, I realized how naïve I had been to think teaching about peaceful protest would be that easy. Despite my planning, I hadn’t considered the deeper questions around activism—who should be leading the movement and who is there to support? The magnet students who led the protest rightfully spoke up against injustice but also didn’t recognize the privilege which placed them in classrooms with better resources and higher outcomes. The Afghan refugees across the hall were terrified by the chaos, something the young protestors hadn’t considered. Once again, the responsibility of being a teacher weighed heavy on my heart.

The documentary Waiting for Superman came out my first year of teaching, and as I sat alone in the movie theater listening to the interviewees bemoan the damage a first year teacher could inflict on their students, I raged at the screen. Did the producers think I didn’t know the risk I was as a first year teacher? That I didn’t worry every day that my lack of experience could change the trajectory of my students’ lives? I’ve always known that the lessons I teach, the books I include in my classroom, shape the outcomes for my students.

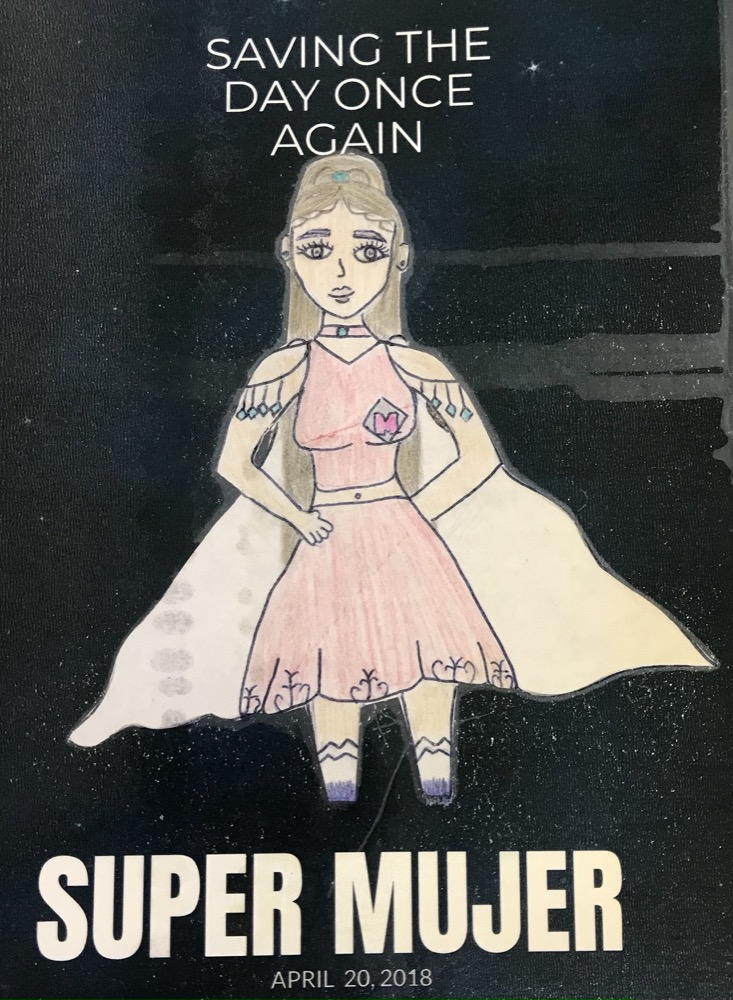

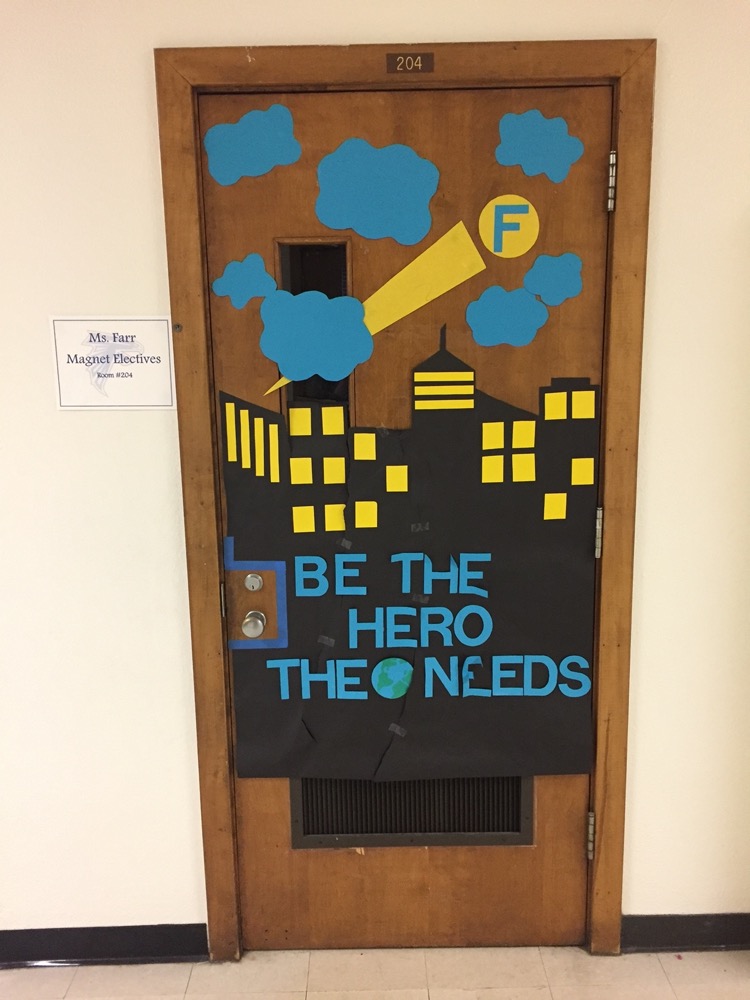

During that same first year teaching, I noticed that the PowerPoint I made to teach the vocabulary of families in my PK Spanish course only included two-parent heterosexual families. That night, while I hurried to remake my slides, I made my first decision to teach with justice. Later in my graphic novels class, I restructured the superhero unit to begin with students identifying the qualities of current superheroes—generally male, white, muscular, able-bodied—and encouraged them to create superheroes that represented themselves. In the monsters portion of the reading elective Heroes and Monsters, I expanded beyond mythological creatures to a study of the people we historically have considered monsters. And of course, I taught that unit on peaceful protest.

I have a responsibility as an author to create stories that entertain and inspire, but also do no harm.

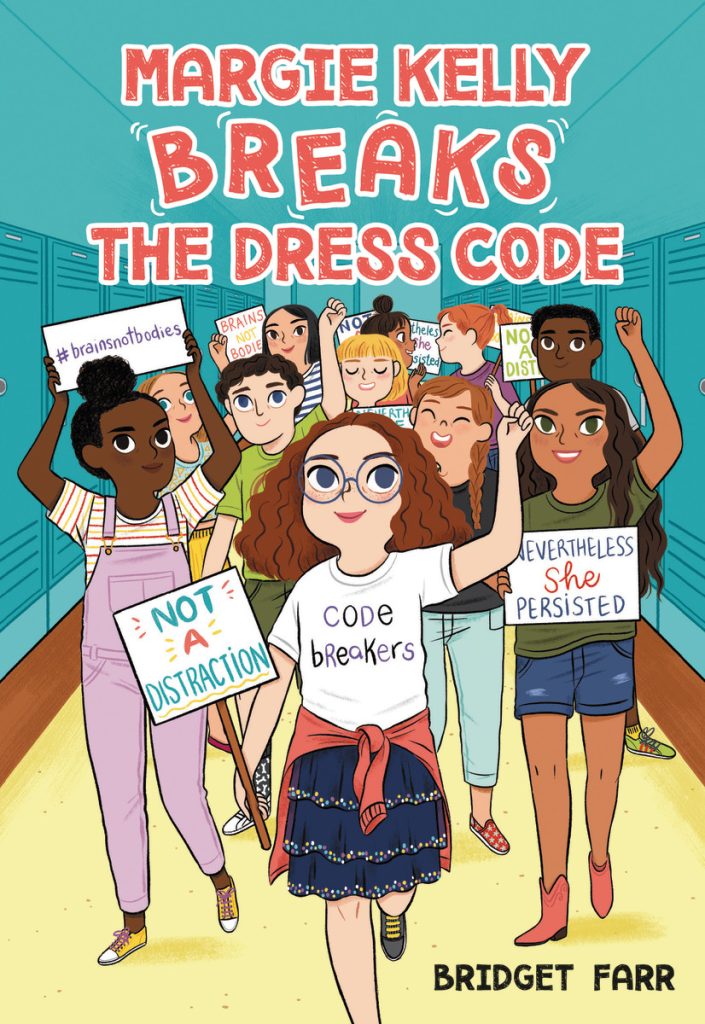

I cannot teach—or lead—without a sense of justice and my writing is the same. In my first novel, Pavi Sharma’s Guide to Going Home, I struggled with her racial representation. While inspired by my South Asian husband, I knew the risks of being a white author writing a protagonist of color. I also worried that making Pavi white would create a white savior as she rescued the other black and brown foster kids. “Just write what you want,” well-meaning friends often tell me, but it’s not that simple. And it shouldn’t be. I have a responsibility as an author to create stories that entertain and inspire, but also do no harm. In writing Margie Kelly Breaks the Dress Code, I knew it would be disingenuous to write a book about dress codes without taking on the racialized aspect of all school discipline and the way privilege impacts how we advocate for change.

Though some have questioned it as censorship, I’m grateful to the authenticity readers who’ve provided feedback on my writing. They help me see outside my experience and ensure that any child who reads my books will not encounter remnants of my biases. Even when I’m familiar with a setting—like the people and experiences of rural Eastern Montana showcased in my upcoming YA novel The Truth about Everything—these readers still looked for stereotypes or limitations.

When teaching students to self-rate using rubrics, I reminded them I would not be there on their first date or job interview to say, “You’re doing great! Definitely getting an A on this one!” They needed the skills to make smart, empathetic decisions on their own. I hope my books help readers in the same way; maybe they’ll remember how a character responded to a situation and choose to do differently. They’ll learn from my characters’ mistakes so they don’t have to make the same ones themselves.

When talking about the challenges of teaching, we often forget how fun it can be. Writing is the same. These two careers give me the greatest joy and inspiration but they come with great responsibility. I strive to work and write with the confidence that when I step aside, my students and readers will be ready to fight for justice in our world.

Books and Resources

TeachingBooks personalizes connections to books and authors. Enjoy the following on Bridget Farr and the books she’s created.

Listen to Bridget Farr talking with TeachingBooks about the backstory for writing Pavi Sharma’s Guide to Going Home. You can click the player below or experience the recording on TeachingBooks, where you can read along as you listen, and also translate the text to another language.

- Listen to Bridget Farr talk about her name

- Listen to an audio excerpt from Pavi Sharma’s Guide to Going Home

- Discover Bridget Farr’s page and books on TeachingBooks

- Visit Bridget Farr on her website, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and GoodReads.

Explore all of the For Teachers, By Teachers blog posts.

Special thanks to Bridget Farr and Little Brown Books for Young Readers for their support of this post. All text and images are courtesy of Bridget Farr and Little Brown Books for Young Readers, and may not be used without expressed written consent.

I really enjoyed this post, Bridget! I especially liked how you realized the bias inherent in the superheroes in our culture and encouraged students to “create superheroes that represent themselves.” I came across this blog after I had finished a blog post and went back and added this quote from your blog to my post, which is https://monavoelkel.com/2022/03/23/happily-ever-now/