Writing for the Courage and Capability of Young Readers

By Maggie P. Chang

“Free beer on Wednesdays only,” the five-year-old dining with me said.

Huh? Why is this child talking about beer? I thought to myself.

“Gugu Maggie, look.” She pointed to a sign that hung on the restaurant wall. “It says, ‘Free beer on Wednesdays only.’”

Oh, she’s just reading that sign… Wait—what?! She can READ?! The last time I’d seen her was over three years ago, when she was just learning to speak in full sentences. Now, she could read full sentences. And boy, was she proud of it! She wasn’t too concerned that she didn’t know what the sign meant, though. This five-year-old was flexing her remarkable reading skills! Which, sure, differ from the literacy skills needed to comprehend what she’s reading. But she’s just in that liminal space of becoming an independent reader.

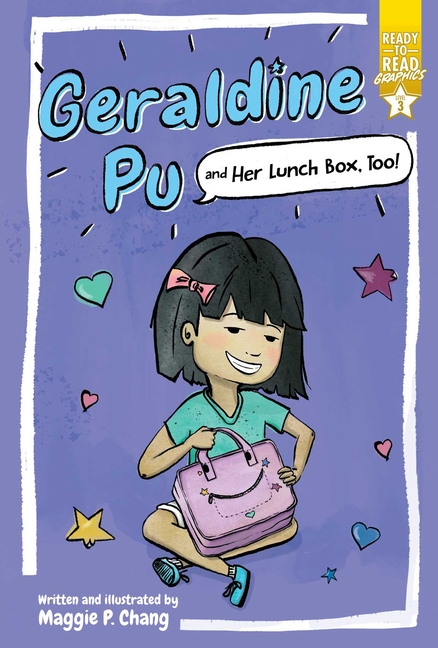

This liminal space is where my new children’s book, Geraldine Pu and Her Lunch Box, Too! lives. As the author and illustrator of this graphic novel for beginning readers, I’ll confess—I was originally apprehensive of the “early reader” category. I feared that transitional phases often came with growing pains. For everyone. Will kids feel forced to read my book and associate the book with feeling frustrated? Can I prioritize telling a good story AND nurturing literacy skills? Plus, what if people still don’t consider graphic novels “real reading” and learning to read is what kids in this category are “supposed” to be focused on?

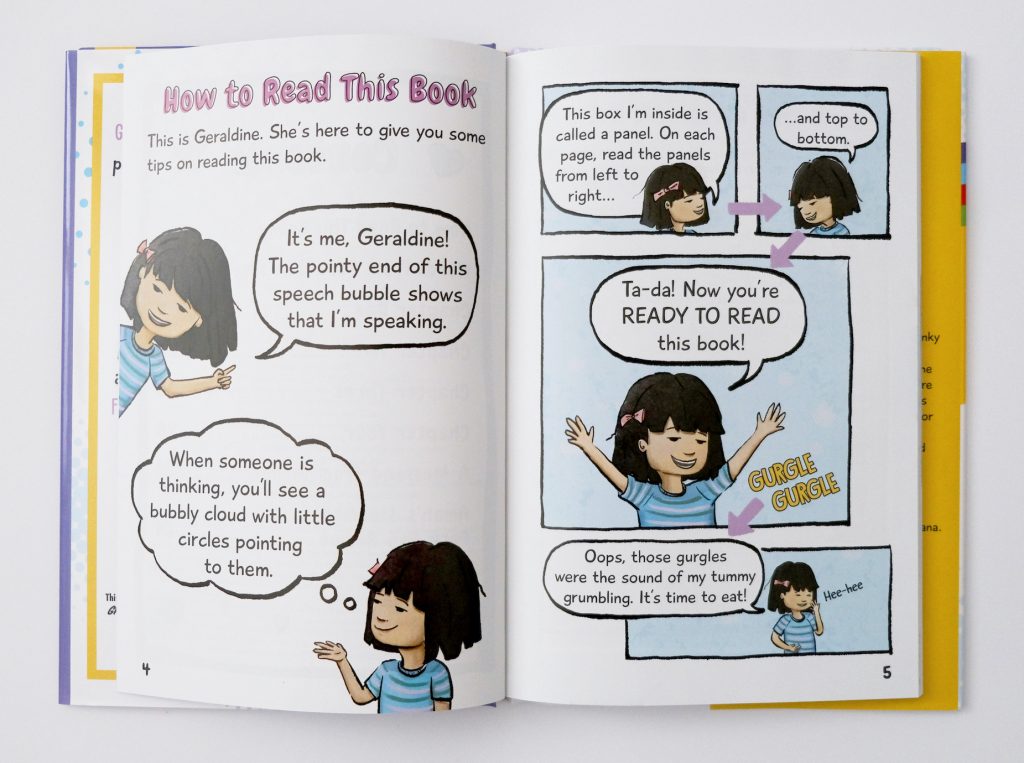

I wondered if my baby (my book) could be whittled down to a picture book. I even toyed with the idea of expanding the narrative and aging the characters for a middle grade graphic novel. But when Simon & Schuster (S&S) described the vision for its brand new Ready-to-Read Graphics program to me, something finally clicked. Their vision was all about giving beginning readers the best introduction possible to the graphic novel format. Their goal—for every reader to come away from a Ready-to-Read Graphics book with greater confidence in their reading abilities. My Geraldine Pu series was all about a child who gains confidence and self-assurance as she grows more independent in her young life. What an encouraging mirror for kids who’ve just embarked on a reading journey! S&S shared how all the books in the program would have easy-to-follow panels, speech bubbles with accessible vocabulary, and a how-to guide for reading graphic novels at the beginning of each book. Then they gave me a heads up that, just like with anything new, pioneering this program could mean extra effort and patience from me—but they wanted Geraldine Pu to be a part of it.

With newfound delight, I accepted the challenge.

As I dove into manuscript drafts and sketches with my editors who specialize in early readers, we thought about what children struggle with as they learn to read and how to support them. Use full sentences. CHECK. Break the story up into enticing page turns and short chapters. CHECK, CHECK. Avoid starting sentences with a coordinating conjunction— “and,” “but,” “or” —except for a few cases where it adds tension or flow to the story. CHECK.

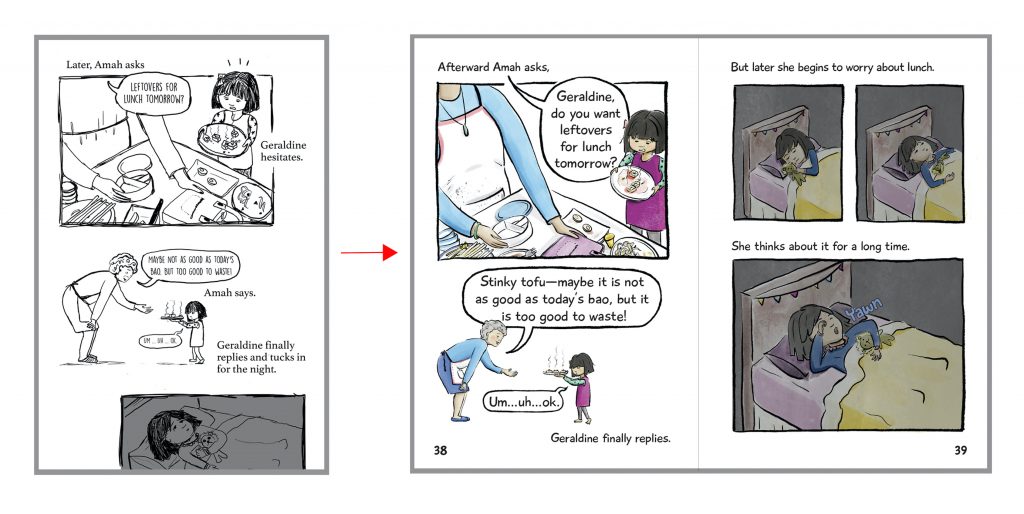

We considered the fact that while young readers labor away at building their first literacy muscles, the graphic novel format has its own distinct learning curve too. Talk about a mental workout! So, we open the book with an engaging “How to Read This Book” guide and an illustrated glossary. We found a sweet spot with layouts—dynamic enough to keep kids’ attention, but simple enough that they avoid overwhelm and eye fatigue. Scenes that used to be a single panel were stretched to a page to give kids a moment to catch their breath. And perhaps the biggest challenge of all—we crafted a narrative that’s authentic and meaningful to children ages 5-8 and what they’re experiencing in their lives. This was the part I was most eager to get right.

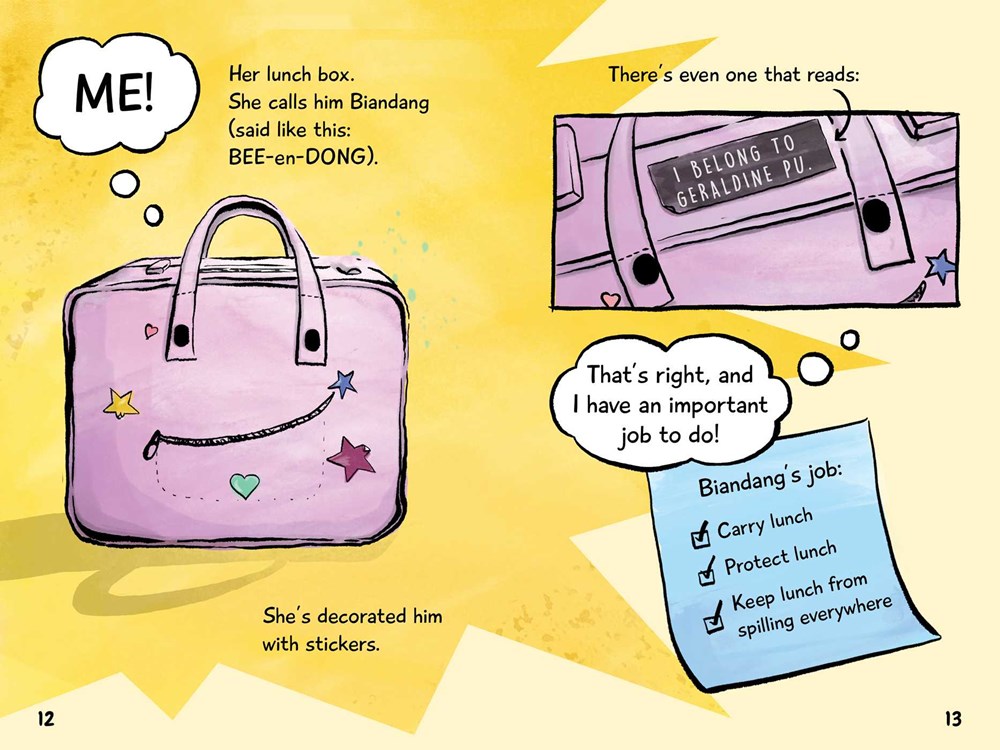

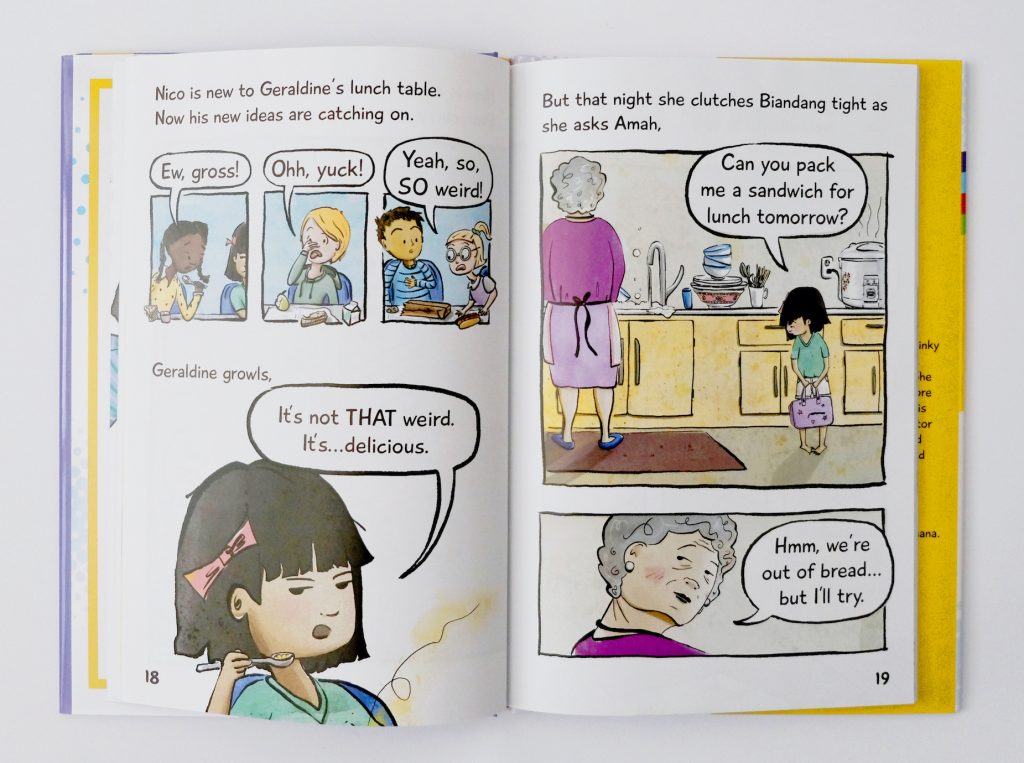

With each book in the Geraldine Pu series, I wrote and drew a story of a spunky, funny, and friendly Taiwanese American girl as she navigates the trials and tribulations of elementary school life—all while she grapples with her cultural and racial identity. Essentially, they’re the books I wish I’d had when I was a kid. The main conflict in the first book is that Geraldine gets teased for the traditional Taiwanese lunches her beloved grandmother, Amah, packs her. Nico, a kid who’s new to Geraldine’s table, calls her curry gross, and soon the rest of her classmates join in. It’s a fresh take on the “lunchbox moment” that so many first and second generation immigrants experience at school. Fearless Geraldine gets rattled, as anyone would. She asks Amah if she could pack her a sandwich for lunch the next day—something I’ve been told that readers of all ages and backgrounds have done in this exact scenario. But the bullying escalates, and so does Geraldine’s anger. Geraldine winds up doing something she regrets big time, but she rights her wrongs and learns that while it’s ok to be angry, it’s what you do with the anger that’s important.

Keeping in line with the fact that readers of this age are learning to do many things independently, from reading books to solving their own problems, it was crucial to me that Geraldine come up with the resolution for the story. Not Amah, a teacher, or any other adult. And while I make it apparent that the grown-ups in Geraldine’s life make her feel loved and supported, the book also says to kids—I acknowledge that you’re a capable human.

I recall wanting to be seen this way as a child—capable. And having spent several years as a teacher, my students confirmed this. In fact, many of my choices for the book were informed by my observations as a teacher. For instance, my students taught me that those who picked on other kids had a reason, even if their actions were hurtful and wrong. So, I didn’t want to make Nico a one-dimensional bully. Instead, the book introduces him as a kid who’s afraid of anything new. He wears only striped shirts and eats the same exact lunch every single day. Because empathy is a big part of the story, I hope that readers understand on some level that Nico is acting out of fear, and even “bullies” have to find their way.

Now that the book is out, it’s been beyond thrilling to hear that kids adore it! I’ve watched videos of them reading it to a grown-up, their staccato voices still needing help with a word here and there, but reading with inflection and feeling nonetheless. They’ve had rich discussions about compassion, being different, trying new food, and standing up to bullies. And kids have even referenced terms and ideas they’ve learned from the book days later. Hurray! Their literacy muscles are growing! As are their social and emotional skills! All while having fun. These young readers show me that while liminal spaces and transitions can be hard, well… they can also be exciting.

I’m reminded of this once again by the five-year-old girl who can now read signs about free beer. After lunch, she and her mom and I go to a park so the girl can ride her bike. Her heavy, clunky two-wheeler and her recent sense of balance make for a choppy start to the ride. At one point, she teeters over, and I pull the bike off of her sweaty torso. She continues on. She pedals, pauses, ponders. Then back to pedaling some more. Until finally, she’s cruising—she’s free.

Well, almost.

She rides just far enough to where she can still see me and her mom who are trailing behind her. She sets both feet on the sidewalk, looks back at us, and waves as we cheer. Then ecstatic, she keeps riding. Glowing, growing, on the path to independence.

Text and images are courtesy of Maggie P. Chang and may not be used without expressed written consent.

Leave a Reply