From Teaching to Writing

TeachingBooks asks each author or illustrator to reflect on their journey from teaching to writing. Enjoy the following from Matthew Burgess.

When I step into a second-grade classroom to kick off a new poetry program, the students see me as the teacher. I’m tall, I stand where their teacher stands, and I’m leading the lesson. But as I look around at their faces and begin to learn their names, I know that many of these students will become my teachers in turn. Angie will educate me about the limitlessness of daydreaming; Salvador will dash off profundities without the slightest hint of self-consciousness; Cecilia will teach me patience. And all of them—each class I’ve visited in the last two decades doing this work—put me back in touch with the child I was.

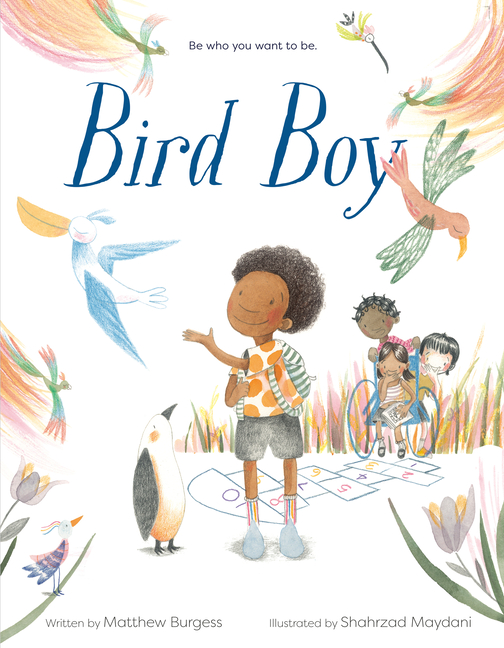

Nico, the hero of my new picture book Bird Boy, is also my teacher. In some ways, he is a version of myself—my nickname was “Bird” in elementary school, and I remember peeling away from the pack to sit solitary in the grass and daydream. But unlike Nico, I passed too many hours worrying whether I fit into the mold of what I was “supposed to be.” How many children inwardly fret that they might be dangerously strange or irreparably different? For me, Nico’s quiet heroism is that he is able to stay on his own side. He connects with an inner knowingness that allows him to be “both a bird and completely, delightfully himself.” Nico’s imagination doesn’t falter when the insult flies his way. On the contrary, he soars.

When asked about the connections between my teaching and the writing of Bird Boy, my mind returns to a central question that informs, shapes, and motivates my pedagogy: Why does the exuberant creativity of childhood fade over time? What contributes to this diminishment, and how might we prevent and/or repair it? Clearly, a nuanced response to this question is beyond the scope of this piece. Instead, I offer Nico as the gentle and joyful bearer of one potential antidote.

The goal is to encourage students to keep opening up to creative exploration, to trust their own questions, and to harness the energy that comes when we strike a meaningful balance between process and product.

All children play and write and draw and sing, and these fundamental human activities bring us happiness and excitement. Children radiate this aliveness. But over time, we learn that our playing and writing and drawing and singing are supposed to look or sound a certain way, and if we do not sufficiently reproduce the models with which we are presented, then we fall short—or fail. As we internalize the judgments of others and become anxious over products and outcomes, we step outside of “process.” The spontaneous flow of creativity and curiosity and delight becomes interrupted—or blocked entirely.

I have another book publishing this summer titled Make Meatballs Sing: The Life & Art of Corita Kent. In addition to being a celebrated Pop Artist and nun, Corita was a tremendously innovative educator. While rereading one of her books recently, titled Learning By Heart: Teaching to Free the Creative Spirit, I discovered the following passage: “Small children have almost endless imaginations… Imagination often gets stamped out by the need to conform, and the older the child sometimes the harder it is to get him to revive his early gift. By ingenuity of assignment the teacher can open up what has been narrowed down.” She also writes: “As teachers we try to participate in the process of empowering people to be the artists they are.”

This is what I try to do with all my students, both in the early elementary classrooms and at Brooklyn College: to design assignments, activities, and structures that combine form with freedom, work and play, attention to detail with freedom of expression. The point is not to adopt an “anything goes” approach—far from it. The goal is to encourage students to keep opening up to creative exploration, to trust their own questions, and to harness the energy that comes when we strike a meaningful balance between process and product. When we feel connected to what we are learning and making, we are more inclined to follow through.

What does this have to do with Nico? At the beginning of Bird Boy, Nico is “nervous walking the path to class alone with a backpack full of stones.” But rather than twisting himself into some tight corner to fit in, he persists in doing what he loves to do. Even when he is called out for it in a teasing way, he follows his imagination rather than his fear. He lets go of that heavy backpack and lifts off.

Books and Resources

TeachingBooks personalizes connections to books and authors. Enjoy the following on Matthew Burgess and the books he’s created.

Listen to Matthew Burgess talking with TeachingBooks about the backstory for writing Bird Boy. You can click the player below or experience the recording on TeachingBooks, where you can read along as you listen, and also translate the text to another language.

- Listen to Matthew Burgess talk about his name

- Discover Matthew Burgess’s page and books on TeachingBooks

- Visit Matthew Burgess on his website, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Explore all of the For Teachers, By Teachers blog posts.

Special thanks to Matthew Burgess, Random House, and Blue Slip Media for their support of this post. All text and images are courtesy of Matthew Burgess and Random House, and may not be used without expressed written consent.

Matthew, whatever happens with our book, I am so pleased to meet you through your books and interviews .

” I (too) know that many of(my) students (have) become my teachers…”

“…to encourage students to keep opening up to creative exploration, to trust their own questions, and to harness the energy that comes when we strike a meaningful balance between process and product” profoundly mirrors my intentions and the tone of The Poetry Studio from which the poems were written in Another World.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful to meet in Vermont sometime when you are visiting Chard.

With gratitude,

Ann Gengarelly