On Rhyming, Creativity, and Engineering

By Yvonne Ng

Rhyming and Engineering

The first time I put engineering and rhyming together was when I wrote a Letter to the Editor of my college paper. It was a response to a recent editorial that stereotyped engineering students as grinds who just didn’t fully appreciate the liberal arts education of our school.

Sure, engineers would earn tons more money when they graduated, the editorial said. But what had they really learned, besides working hard and lots of science and math? They were uncolorful, uncultured workaholics. Well, that’s the impression I got when I read it.

I was both defensive and a bit upset. We engineers were fun! We were creative! Didn’t the author know that many of us chose to attend our college (instead of M.I.T.) because of the liberal arts? (Sorry, that was a stereotype of our colleagues from there!)

But I realized I was in a pickle. A well-argued letter back would have likely been labeled “the engineer doth protest too much” and would end up proving the author’s point. I needed another approach. So I leveraged all that I had learned about solutions (from engineering), people, prejudice, and change (from the liberal arts) and came upon a unique strategy, certainly not one normally done in an intellectual debate or discourse.

I was (and still am) a long time fan of Dr. Seuss. I wrote my 11th grade research paper on Theodor Geisel, and when he died, I got condolence wishes from a surprising number of friends. I had also subscribed to the I Can Read book club while in college. My roommate teased that it was for our fictional child, Yvonne, Jr.

I set out to show (not argue) that engineers (at least at our school) “got” the liberal arts: I wrote a Seussan poem and submitted it to the paper. Here are the first few lines:

Sally, Me, and the B.S.E

With apologies to Dr. Seuss and serious poets

The sun did not shine.

(It was a New Jersey day.)

So we sat at the table,

Just rambling away.

I sat there with Sally.

We sat there, we two,

And I said, “I detest

The recession, don’t you?”

“So few jobs in the country

And so little preparation.

When we leave Princeton’s bubble,

Will we have a vocation?

All we do is

Read

Heed

Talk

Walk

And write.

Will we survive a real world’s week night?”

Creativity and Engineering

The poetic approach was a big hit. Engineers stopped me and thanked me for responding. The author (who was actually a friend) hugged me and said I really helped them out on a slow news day.

How hard was it to write? They asked. It must have taken forever.

Not really, I responded. I actually cheated and followed The Cat in the Hat structure, tone, and rhythm pattern so closely I wondered if I was plagiarizing.

What folks don’t realize is that engineering teaches us to be creative within constraints. We don’t do well with a blank piece of paper and anything we could dream up. We thrive when we have constraints like: You can only spend this much money. You can only use these materials. Or the favorite: You only have this ridiculously short period of time.

The liberal arts were just another set of tools in my toolbox to solve problems I cared about. They gave me insight not only into what the problem to solve was, but they gave me the skills to address them—though probably in ways you wouldn’t expect.

It’s under constraints that the best of an engineer comes out: You have to tap into everything you ever knew that might help. Arts projects you did as a kid. Patterns you noticed and observations you made when you were hiking or watching Mom cook that amazing meal or Dad throwing that curve ball you could never hit. And you welcome being on a team, because now you can tap into more people’s memories, experiences, and talents.

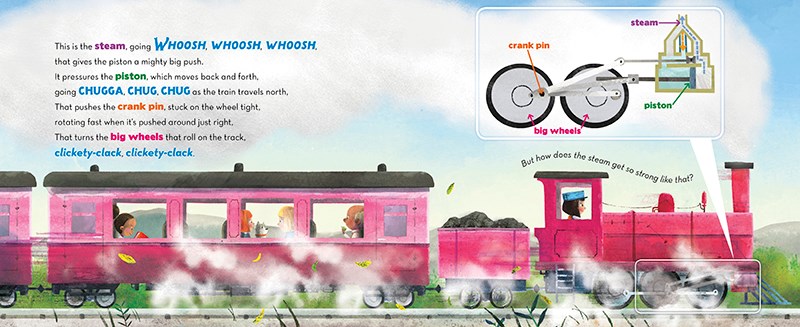

When I taught elementary teachers engineering, I found there were some concepts and practices that they were missing—the childhoods of people differ vastly, with some being useful in developing an engineering way of thinking. The books I create all try to situate these engineering gaps in the familiar: The Mighty Steam Engine nestles engineering drawings in the world of nostalgic train travel and demonstrates a simple exercise of reverse engineering. They’re Tearing Up Mulberry Street reveals the engineering material selection and design considerations in the context of road construction and its machines that is often witnessed on a daily basis (certainly during the summer months in Minnesota!)

I’ve found that I’m particularly good at coming up with rhymes around very technical terms, though my editor made me eliminate viscous from my latest book because she said it wasn’t age-appropriate. But writing children’s books about engineering is more than just rhyming. The subjects and underlying themes are truly a manifestation of all I learned while in a liberal arts college.

Text and images are courtesy of Yvonne Ng and may not be used without expressed written consent.

Leave a Reply