From Teaching to Writing

TeachingBooks asks each author or illustrator to reflect on their journey from teaching to writing. Enjoy the following from Desmond Hall.

My first year as a high school teacher was intense. I taught biology in East New York, Brooklyn, and that area had the highest homicide rate in the country at that time.

I remember giving my first quiz, and a student came to me and said something like, “Mr. Hall, I can’t take your quiz because they were shooting too much last night.” I didn’t say anything at first. I was totally unprepared to hear what she’d just said. This was no “a dog ate my homework” excuse. Then another student said she lived in the same neighborhood, and indeed the shooting was excessive the night before. This wasn’t a singular event, either. A lot of students in that school district had to deal with circumstances that no young people should have to.

But even with all that stress and dissonance, or maybe because of it, many students kept repeating one particular mantra. They all wanted to know how the material was relevant to their lives. I also taught in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, a school district that wasn’t fraught with the same social issues, and still the students wanted to know how the material was relevant to their lives.

They need to see themselves as they’re deciding who they are, who they want to be, and what kind of career they might pursue.

All those experiences that I had in the classroom refined my understanding of the importance of relevance, in particular, cultural relevance. And I brought those learnings to my work as a young adult writer. And to that end, I’m so happy that there is a movement now to publish relevant stories for diverse audiences. I even think of my own daughter’s experience in the classroom. Her high school teacher asked her to define a book that she was reading as either a “window” or a “mirror.” The book that was a “window” allowed the reader to have a view onto a life experience that was different than one’s own. The book that was a “mirror” reflected one’s own life experience. And I think teenage years are precisely the time when young people need “mirrors.” They need to see themselves as they’re deciding who they are, who they want to be, and what kind of career they might pursue. And unfortunately, children of color have not traditionally had these “mirrors.” They’ve been deprived of the opportunity.

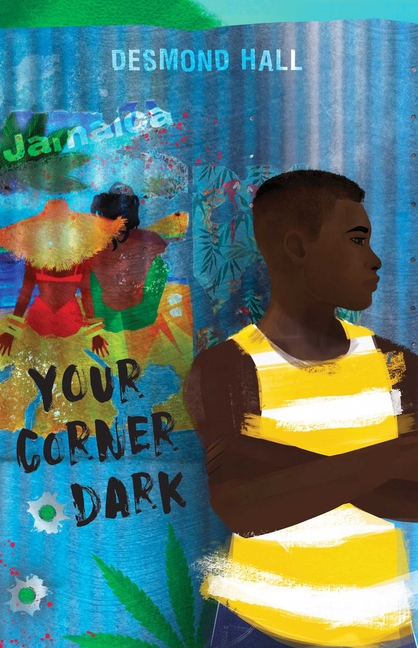

In my YA novel, I tell a specific Jamaican story that has a universality. It’s about what a Jamaican teen will do for the sake of family.

The title, Your Corner Dark, is a phrase in Jamaican culture that refers to being stuck between a rock and a hard place with no good choices. And my story has often been described as a fast-paced, riveting page-turner that’s exactly about choices, impossible odds, and perseverance—and you’ll read it with a knot in your throat and hope in your heart. I love that description because it’s exactly that type of book that can get teens who aren’t so psyched about reading into reading. Also… I love fast paced books myself.

All those experiences that I had in the classroom refined my understanding of the importance of relevance, in particular, cultural relevance.

My protagonist, Frankie Green, is a Jamaican teenager who gets a full ride scholarship to study in the U.S. and shortly after, he faces a sudden tragedy that threatens everything he’s dreamed of, and his very life. Frankie’s father is struck by a stray bullet, and Frankie is forced to join his uncle’s posse to get quick money to pay for his father’s medical treatment. It’s a devil’s deal.

And the cast of secondary characters in Your Corner Dark faces their own ethical dilemmas as well…

Leah, Frankie’s girlfriend, an upper middle class art student, struggles with their societal differences, as well as her own creativity. Her artwork is very political and works of that nature are not received well by the professors at her school. She also struggles with her depression and struggles to be open about her condition.

Jenny is Frankie’s aunt, and if this were a movie she would be up for best supporting actress. Jenny works in her brother’s posse as an enforcer and negotiator. She battles to rise up in the hyper-masculine world of the drug trade.

Samson and Joe, Frankie’s father and uncle, respectively, are locked in a Cain and Abel style battle—with Frankie’s soul as the main prize.

In addition, I think my experience as a teacher made me focus on integrating social issues into my writing, which is a responsibility that falls on the shoulders of all teachers.

One of those issues is the father and son relationship, and how it pertains to defining Black masculinity. Frankie’s father has a very traditional view of masculinity that is common among many Jamaican and Black American men of a particular generation. In one instance, Frankie’s father admonishes Frankie because he cries at his mother’s funeral. His father thinks the act of shedding tears is unmanly—even though this occurs at the funeral. Also, Frankie’s uncle Joe pushes him to be tough and unforgiving, and even ruthless. But through it all, Frankie has to choose what kind of man he will become.

Another issue that has particular relevance to both Jamaican and American life is police brutality. In Jamaica, there is a long-standing issue with police violence, and over the last decade organizations like Amnesty International have called for a cessation of extrajudicial killings carried out by the Jamaican defense force.

Your Corner Dark also discusses the issue of colorism. The lasting impact of colonialism has created a desire for having lighter skin color—to the point where some Jamaicans use bleaching products to make their skin lighter because they think they will be treated better. In fact, the issue has become so prevalent that the national soccer program screens players when they come back from playing abroad because their bags may be packed with bleaching products.

Your Corner Dark is set in a fictional election year that becomes combustible. Jamaica has a political history where the two-party system, the equivalent of Democrats and Republicans, uses gangs to influence the vote. This has been tamped down but it still exists in a subtler, but potentially deadly way. And because Frankie becomes involved in a gang that tries to influence voters, we get a visceral POV on the political issues.

And lastly, Your Corner Dark touches on teenage depression. As I mentioned earlier, Leah, Frankie’s girlfriend struggles to be open about her condition, when Jamaican society as a whole urges those with depression to deal with it in silence.

I love that there are so many important topics in the book that could stimulate robust debate in the classroom. And because these topics are so important I believe adults will also appreciate the read.

I hope you read Your Corner Dark, and become riveted by Frankie’s story and life in Jamaica that occurs far beyond resort walls, where you can see that Jamaica people are not monoliths. If you’re interested in teaching the book, Simon and Schuster has prepared an awesome reading group guide. You can find it here.

Books and Resources

TeachingBooks personalizes connections to books and authors. Enjoy the following on Desmond Hall and the book he’s created.

Listen to Desmond Hall talking with TeachingBooks about the backstory for writing Your Corner Dark. You can click the player below or experience the recording on TeachingBooks, where you can read along as you listen, and also translate the text to another language.

- Listen to Desmond Hall talk about his name

- Explore TeachingBooks’ collection of activities and resources for Your Corner Dark

- See a Reading Group Guide for Your Corner Dark

- Discover Desmond Hall’s page and books on TeachingBooks

- Desmond Hall on his website, Facebook, and Twitter.

Explore all of the For Teachers, By Teachers blog posts.

Special thanks to Desmond Hall and Simon & Schuster for their support of this post. All text and images are courtesy of Desmond Hall and Simon & Schuster, and may not be used without expressed written consent.

Leave a Reply