From Teaching to Writing

TeachingBooks asks each author or illustrator to reflect on their journey from teaching to writing. Enjoy the following from Carrie Firestone.

I spent nearly a decade teaching U.S. history and government at a Manhattan high school to students from more than thirty countries. We worked hard, often meeting at school during off-hours to prepare for the New York State exams.

We had few resources back then. I remember linking arms in front of the basement book room with my fellow teachers, demanding the administration allow us to forage for old textbooks. There was always a line for the one copy machine where, if we were lucky, we could copy one or two coveted pages of a book to gift our students. The restrooms rarely had soap, paper towels, or even toilet paper, and it wasn’t unusual to work through the smell of dead wall-rodent.

In winter, we were always too hot or too cold. There was no “just right” in a building with bones as old as our school. In summer, during long evening summer school classes, our assistant principal would carry a tray of ice cubes from room to room, and we taught and learned with ice cubes resting on the top of our heads, dripping into our faces.

Our collective value system was simple: This is a safe space. We are here to work together. We will treat one another with kindness and respect.

We made our own rules. If people were hungry, they ran across the street to the deli. If I was hungry, someone ran to the deli for me. Students ate and drank in class, ran in late, missed long stretches of school to take care of life business. Our collective value system was simple: This is a safe space. We are here to work together. We will treat one another with kindness and respect. We were a close community, bound together by a common goal, and our students achieved remarkable success despite the odds.

Their stories reflected the wars, famines, and natural disasters of the moment. They came from Vietnam and China, Haiti and the Dominican Republic, Poland and Bulgaria, Bangladesh and Pakistan. They were Uzbeki Jews escaping persecution, West Africans escaping political unrest, and Yemenis searching for work. At one point, I had thirty-eight students from thirty different countries in one class.

When I reflect on how my teaching influenced DRESS CODED, I think about the fact that not once, in all my years of teaching young people, did I stop to notice what my students were wearing.

Were they eating?

Were they making it to school?

Were they getting by?

Were they learning?

Was I doing everything I could to help get them through the day?

I thought about all of those things. But I never once thought, “Is this student wearing appropriate clothing?”

My years of teaching taught me that schools, teachers, students, and entire educational systems can thrive without ever discussing, or even noticing, what students wear.

***

Fifteen years after I left my beloved New York school, my own children started middle school in suburban Connecticut. At first, I didn’t pay attention to the comments about the dress code coming from the back of the mini-van. Then I overheard a conversation about an eighth-grade student who was pulled out of class, chastised, and forced to call her mother to bring a change of clothes because her off-the-shoulder blouse was “unacceptable.” She later wrote about her experience, about how she felt herself hunching over, covering her shoulders with her hair, trying to make herself invisible.

I began to interview middle school students from a number of districts. Their stories were disturbingly similar. Teachers and administrators belittling them, shaming them, labeling them “distractions.” Staff members forcing them to miss class, to become public spectacles, to choose between being comfortable and being “good.”

The inciting incident that inspired me to run home and start writing a book about unfair school dress codes happened during a conversation with a school administrator. When I asked him why some of his staff members were so fixated on dress coding middle schoolers, he replied, “Well some of these girls make me uncomfortable.”

“Some of these girls” were twelve years old.

Most of us encounter occasional moments where we feel judged or self-conscious about what we are wearing. I remember being asked to remove my shoes in a situation I hadn’t expected. I spent the entire day wondering if people were noticing my giant, un-pedicured feet. I couldn’t concentrate on my work or my social interactions. All I could think about was ‘are people staring at my feet?’ I often wonder, what if I had to contend with that feeling every single day? What if attached to that feeling were the looming specters of power and misogyny? What if the threat of someone stopping me in the hall to publicly call out my clothes began to erode my confidence and drill into the very foundation of how I viewed myself?

I learned in my research for DRESS CODED that the fear of that feeling of mortification is a daily source of anxiety for many young people. They are asked to change their clothes in the middle of the school day, or wear clothes that aren’t comfortable. Even worse, students are told they are a “distraction,” a term that is both dehumanizing and demoralizing.

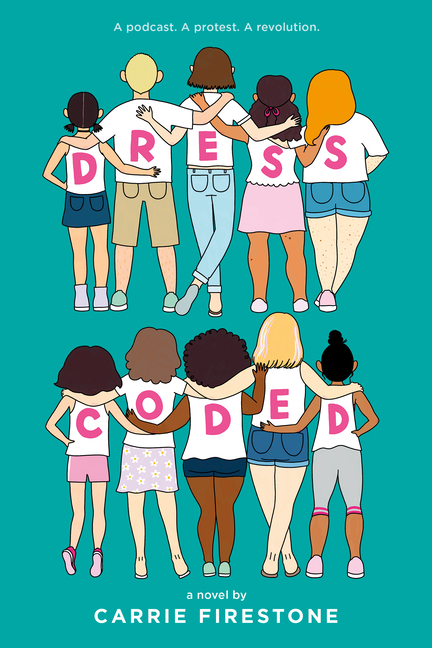

DRESS CODED is a novel about an eighth grader who starts a podcast to protest the unfair dress code enforcement at her middle school and sparks a rebellion. I wrote it to start a conversation. I hope young readers will see themselves in the characters and know that, like the main character Molly and her friends who ultimately work to change their unfair school dress code, there are ways to change systems that dehumanize and demoralize us.

It isn’t easy to acknowledge the things we were raised to believe. It’s even harder, sometimes, to fight systems from within, especially when we are stretched to capacity.

I hope teachers will initiate conversations about why we are so often compelled to police and criticize what our students choose to wear. It isn’t easy to acknowledge the things we were raised to believe. It’s even harder, sometimes, to fight systems from within, especially when we are stretched to capacity. But, the impact of bringing the dress coding conversations into classrooms and teachers’ lounges goes well beyond “what are our students wearing?” Whether you are a “I never think about what my students wear” person, or a “I firmly believe in dress coding my students” person, there is value in open-minded discussion. I hope DRESS CODED offers a place to begin.

#DressInPeace.

Books and Resources

TeachingBooks personalizes connections to books and authors. Enjoy the following on Carrie Firestone and the books she’s created.

Listen to Carrie Firestone talking with TeachingBooks about the backstory for writing Dress Coded. You can click the player below or experience the recording on TeachingBooks, where you can read along as you listen, and also translate the text to another language.

- Listen to Carrie Firestone talk about her name

- Explore TeachingBooks’ collection of activities and resources for Dress Coded

- Hear an audio book clip from Dress Coded

- Discover Carrie Firestone’s page and books on TeachingBooks

- Carrie Firestone on her website, Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter.

Explore all of the For Teachers, By Teachers blog posts.

Special thanks to Carrie Firestone and Penguin Books for Young Readers for their support of this post. All text and images are courtesy of Carrie Firestone and Penguin Books for Young Readers, and may not be used without expressed written consent.

I remember in the mid-1960’s (that dates me), I was sent to the principal’s office because my skirt was too short. It came above my knees. This memory is still clear in my mind when many from my high school years have mercifully faded. I was mortified, especially as my mother taught in the school and I guess I was expected to be a model student. I think what saved my dignity to some extent was that my father, a minister, simply drove another skirt to school, said nothing, just handed it to me with the equivalent of a shrug, and that was that. If he didn’t care, I didn’t care that much. I’ve laughed about this incident for a long time and related it to my son whose school instituted uniforms in grade 11. He was so put out by having to wear the uncomfortable shirt and pants, that he wore those clothes to shreds before he graduated. I’m surprised more pressure was not put on him to buy a second set. Dress codes have presented problems for decades and affect the guys too, at least some of them. I’m quite interested to read your book.

I also remember 60’s and in first grade, the principal would come in with a ruler to measure the girls’ uniform skirts to make sure they were long enough. The girl next to me would roll her skirt up every day and was made to put her hands on the desk and got a whack with the ruler. I’ll never, ever forget that abuse as long as I live.