From Teaching to Writing

TeachingBooks asks each author or illustrator to reflect on their journey from teaching to writing. Enjoy the following from Aisha Saeed.

Ever since I was little, I’d known what I hoped to do with my life. I wanted to tell stories and I dreamed of becoming a teacher. As a kid, I filled up countless spiral notebooks with tales of friendship and adventure. And most weekends you’d find me on the back porch by the chalkboard mounted against the wall, with an array of stuffed animals (and two little brothers) lined up for the day’s lesson on an assortment of subjects from addition and subtraction to the alphabet. I dreamed of the day I’d have a classroom of my own.

Years later, my dream of becoming a teacher came true. I graduated with a Bachelors and Masters in Elementary Education from the University of Florida and began teaching second grade. During my time as an educator, many of the children I worked with were refugees from all over the world. So many of these kids, merely seven and eight years old, had witnessed unspeakable tragedy and heartbreak at such a young age. Saira** and her family had fled Afghanistan after the Taliban made life unbearable and crossed over to Pakistan where they lived for years in tented refugee camps. Her eight-year-old brother Rehan sold tea barefoot in the bazaars to make ends meet until their visa to the United States came through. Shahid lost his father to an IED explosion, and lived in a two-bedroom house outside of Atlanta now with his widowed mother and seven siblings. These are just a few stories of the many children I worked with, and yet despite everything they had been through, these children stepped inside my classroom each day smiling and eager to work. They were endlessly curious, asking for more and more assignments so they could get a better handle on the language. They were endlessly filled with hope.

At the playground during recess I’d watch them swing from the monkey bars, slide down the slides, and talk about the dreams they held for their future. Teacher, doctor, nurse, pilot, congresswoman. These children had all been through horrific circumstances, and as difficult as this was and as drawn as their faces would grow when they shared with me their pain, they did not give up. They were, in my view, the very definition of bravery and resilience.

Though I never set out explicitly to write children’s books, this was the voice of the characters who spoke to me and whose stories resonated deeply within me.

Years later, taking a hiatus from work while I tended to my newborn son, I turned to my other dream. Storytelling. Though I never set out explicitly to write children’s books, this was the voice of the characters who spoke to me and whose stories resonated deeply within me. I imagine this is in part due to my background as a teacher. I’d seen firsthand how a book resonates with young readers. I also know from my own experience as a young reader that the stories read during those middle grade years are the ones that stay with children for many years to come, if not a lifetime.

I finished my first novel and had signed with an agent who was sending it out on submission to publishers. As I waited for word from publishers, I began to wonder what my next story might be. My books always begin with a voice first—and as strange as it sounds—the main characters tend to simply arrive to me asking me to tell their story. A girl had begun to emerge in my mind’s eye. I knew she lived in Pakistan, in a village similar to my own ancestral one, and I knew she was the eldest daughter. But beyond that, I had no idea what sort of shape the story would take.

One day, in 2012, as I read the news, my young son napping just across from me, I came across a story from Pakistan. A teenager named Malala, who had been an outspoken advocate for education had been shot point blank in the head by the Taliban. They resented her for sharing what was happening in her community, the schools that were being shut down. And they aimed to silence her with a bullet.

Like so many around the world, I followed her journey. I waited and wondered and prayed, hoping she would make it through. She did. And instead of letting the Taliban silence her, Malala used her newfound platform to continue to advocate for education for all children around the world. She has since won the Nobel Peace Prize and is a household name. Her story is taught in classrooms around the world.

Like practically everyone, I was amazed and awed by Malala’s bravery and all that she had done. But I also began hearing another part of the discourse that gave me pause. The headlines that touted Malala as one shining light in Pakistan. Articles that implored we needed more people like Malala.

Malala was indeed brave and a shining light. But she was not the only light in Pakistan, nor was she the only brave person who hailed from that country. To her credit, Malala never painted herself out to be “the one and only” brave voice from her birth land. At her Nobel Peace Prize acceptance, she said “I tell my story, not because it is unique but because it is not, it is the story of many girls.”

The danger of painting Malala as “the one and only” was that in doing so, her bravery was classified as unusual. An exception. But Malala’s bravery was not uncommon in Pakistan. There were many courageous kids such as Kainat Soomro, Iqbal Masih, and Aitzaz Hasan Bangas, to name just a few. These were children who were brave in the face of untold difficulties and some had lost so much, including their own lives, in the pursuit of justice. And of course, I knew brave children in my own life. The children I taught. Not a single one of my students saw their names in a headline—but their bravery and resilience mattered and had ripple effects that went on to the world at large.

I wanted to take readers beyond the scary headlines and share with them the Pakistan that I knew: one filled with sugar cane fields and orange groves, delicious food, and warm close-knit families.

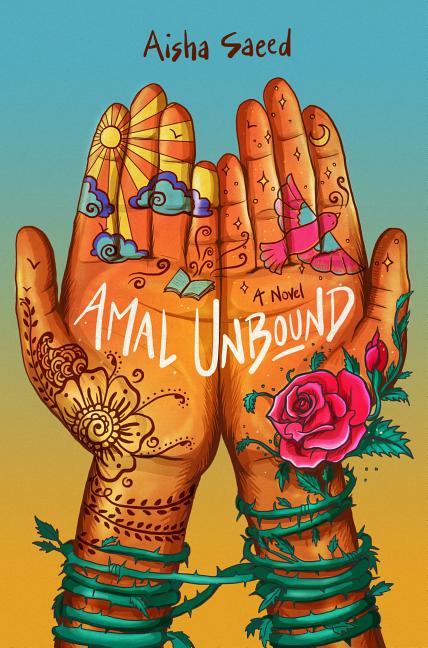

From there an idea was born. I wanted to tell a story set in Pakistan, the country of my ancestral roots, and one that was very misunderstood in the west. I wanted to take readers beyond the scary headlines and share with them the Pakistan that I knew: one filled with sugar cane fields and orange groves, delicious food, and warm close-knit families. I also wanted to tell a story that honored the many children who passed through my classroom. In Amal I was proud to share a character who was strong yet vulnerable. A character who was brave, though her bravery would never make national news. I wanted to write a story that honored the many children who persevered.

Though I do not teach in a traditional classroom anymore, I am grateful to be invited into classrooms around the country to engage in writing workshops, and to speak about Amal Unbound (Penguin, 2018). I emphasize to the children I meet that bravery does not always translate to a headline—in fact, most of the time it does not—but our actions large and small in the name of justice and to improve our communities still matter. I hope Amal Unbound is an opportunity and an avenue for these sorts of conversations in classrooms everywhere.

** all names and identifying details have been changed.

Books and Resources

TeachingBooks personalizes connections to books and authors. Enjoy the following on Aisha Saeed and the books she’s created.

Listen to Aisha Saeed talking with TeachingBooks about the backstory for writing Amal Unbound. You can click the player below or experience the recording on TeachingBooks, where you can read along as you listen, and also translate the text to another language.

- Listen to Aisha Saeed talk about her name

- Explore TeachingBooks’ collection of activities and resources for Amal Unbound

- Find a Discussion Guide for Amal Unbound

- Discover Aisha Saeed’s page and books on TeachingBooks

- Aisha Saeed on her website, Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter.

Explore all of the For Teachers, By Teachers blog posts.

Special thanks to Aisha Saeed and Penguin Books for Young Readers for their support of this post. All text and images are courtesy of Aisha Saeed and Penguin Books for Young Readers, and may not be used without expressed written consent.

Leave a Reply