TeachingBooks.net is delighted to welcome award-winning author Meg Medina as our featured guest blogger.

Each month, we ask one distinguished author or illustrator to write an original post that reveals insights about their process and craft. Enjoy!

The Unexpected Surprises of Research in Burn Baby Burn: How a 1970s Ad Campaign Got to the Heart of a Novel

by Meg Medina

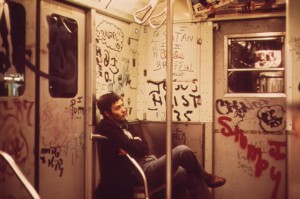

If you visit New York City these days, you’ll likely visit Times Square, picnic in Central Park, and catch a Broadway matinee. Maybe you’ll grab a bite to eat in Harlem, walk happily through Alphabet City, and take subways at any hour of the night. You might even pick up a familiar “I Heart NY” mug.

But nearly forty years ago, in 1977, you wouldn’t have done any of that—except maybe the mug. (I’ll get to that in a minute.)

I was a girl in Queens back then, and I knew a different city, one that was nearly bankrupt and teetering on social disaster. Times Square was a filled with peepshows, prostitutes, and junkies. Garbage spilled onto the streets, and the subways reeked of urine and dust. To add to our daily horror, a serial killer named Son of Sam held us in a state of utter panic as he hunted down young women and their dates with his .44 Bulldog Revolver. And then the crowning touch came in July that year. During a heat wave, an electrical blackout in the city and surrounding boroughs plunged us all into a steamy darkness that unleashed a crime wave we couldn’t have imagined. By the time the lights came back on over 24 hours later, entire neighborhoods had been burned and looted to the studs. More than a thousand fires had been set, and 3,700 people had been arrested. What followed was finger pointing and soul searching over what New York City had become.

How did the city manage to save itself from that?

I thought a lot about the impact of violence as I wrote Burn Baby Burn (Candlewick 2016). My protagonist Nora Lopez would have seen a lot that year, both inside her own family and in situations all around her.

Research gave me plenty of ugly incidents to pull from. I folded in the large historical events—the murders, the blackout—along with the smaller ones that I pulled from the pages of newspapers of the day. A grisly explosion in a Chiclet’s gum factory that blew out four floors and rained spearmint gum and body parts on the street below. Fifteen-year-old Randolph Evans murdered in front of his apartment building by a crazed white cop. A plane hijacked on the tarmac of JFK airport over the Fourth of July.

But with each page, I knew things would have to turn around for Nora. Something was going to have to force her into action. How would that happen?

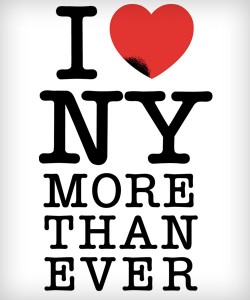

As it turns out, part of the answer was tucked—very improbably—inside one of my favorite research discoveries. The “I Love New York” campaign.

You may not know that famed designer Milton Glaser launched the “I Love New York” campaign that year, something he thought would last only a couple of months.

Mr. Glaser designed the logo pro bono, and it remains one of the most successful marketing campaigns of all time, copied endlessly, including a poignant adaptation after the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center. It is also an ongoing moneymaker for the city, each time it is used on a T-shirt, mug, or ad.

At the time, I might have argued with the sentiment. Broadway stars singing to me about how much they loved New York? Who could possibly love that cesspool? What kind of marketing bull was this, anyway?

But when I came across it in my research, I had to consider its enduring success. It occurred to me that I had missed something important about the roots of resilience in people and in cities.

I think Mr. Glaser’s brilliance was in stripping down our emotions. He forced New Yorkers to ask themselves how they really felt about the place they had always called home.

Do you love this city, this family of people? And if you do, will you stand up for it?

As I wrote about the city and about Nora, I realized that I had to ask my protagonist the same questions, to strip her experience to the essential. Do you love yourself? If you do, how hard will you struggle to save yourself?

Today when I see Mr. Glaser’s logo, I don’t roll my eyes. In a simple red heart, he gave citizens an idea to rally around. We were collectively in crisis, but this tiny graphic gave us a core that we could agree on so that we could do the hard work of rebuilding our home.

Love—as Mr. Glaser instinctively knew, and as Nora Lopez would find out—was the essential engine of transformation.

Listen to Meg Medina’s Audio Name Pronunciation.

Listen to Meg Medina share how she came to create Burn Baby Burn.

See all available resources about Burn Baby Burn.

Text and images are courtesy of Meg Medina and may not be used without her express written consent.

Leave a Reply