TeachingBooks.net is delighted to welcome award-winning author M.T. Anderson as our featured guest blogger.

Each month, we ask one distinguished author or illustrator to write an original post that reveals insights about their process and craft. Enjoy!

Music Meets Military History

by M.T. Anderson

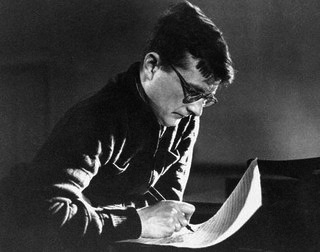

For years, I heard bizarre, thrilling stories about Dmitri Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony; how it was written by the Soviet composer in the besieged city of Leningrad as the Nazis bombed the city; how it was performed there by a starving orchestra while the Red Army shelled the Germans to protect the concert hall; and how it was put onto microfilm and slipped out of the USSR, flown to Tehran, driven across the desert to Cairo, and finally brought to America to interest the United States in the Soviet cause. As a music lover I was deeply moved by a story of the power of a symphony to change history. And I have to admit that, as a children’s book enthusiast, I was intrigued by the Tintin-like tale of microfilm and intercontinental diplomacy. Who wouldn’t be? So I started to ask myself if there was a book for teens there.

I pictured telling this story to those kids I’ve met who are so passionate about music (any kind of music!) or the arts – the drama kids, the band kids, the writing kids, the painting kids … or, for that matter, the military history nerds out there who, like me, love poring over maps of battle plans and hearing about the specs of Stuka diver-bombers. Those are usually two separate groups, but in this case, here was a story that brought them all together.

Quietly at first, while working on other things, I started to read biographies of Dmitri Shostakovich and histories of the Soviet Union. I was shocked and amazed by what I found. This is one of the great things about research: No matter how much you think you know, there are still whole worlds to be discovered. Russian literary, musical, and artistic history was full of mind-boggling experiments by artists I’d scarcely heard of. And when it came to the military history, I discovered a lot of things I knew about the Second World War were wrong or just ignorant. I’d never before comprehended the full depth of the Soviet sacrifice. About 27 million Soviet citizens died during the war. Seventy thousand Soviet cities, towns, and villages were razed to the ground and simply ceased to exist. The suffering and endurance of these people in the face of the Nazi terror overwhelmed me. Revelations like these strengthened my resolve to tell the story of the Russian war experience, so often ignored or passed over in American accounts of the conflict.

At first, I assumed I’d be writing a book of pre-digested history, a popularization of things “real” authors had already discovered. Many years ago, that’s how people thought of nonfiction books for young people. But the world of nonfiction has changed, and, as author/editor Marc Aronson has spent the last decade pointing out, authors for kids are increasingly doing their own research. Writers like Phillip Hoose, Betsy Partridge, Ellen Levine, Tanya Lee Stone, Sue Bartoletti, and Marc himself take it for granted that they’ll be writing about things that “adult” authors haven’t necessarily investigated.

So when I discovered that no musicologists had ever really looked into the story of the microfilm transfer across the deserts and oceans to the shores of America, I took it as a challenge. The evidence was scanty. I scanned footnotes and wrote to Shostakovich scholars all over the world, but could find almost nothing. I spent days following a false lead in the United Nations archives in New York City. No dice.

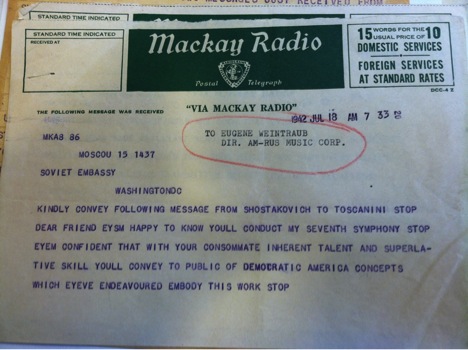

Of course, the nature of research has profoundly changed in the last ten or fifteen years, and in the end, it was clues yielded up by online searches that led me to the old-fashioned print-and-paper trail. An archived Billboard article from the 1940s gave me the name of Shostakovich’s American talent agent, Eugene Weintraub. I discovered his son, writer and nature photographer David Weintraub, had generously donated his papers to the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

There, sitting in front of a box of letters representing fifty years of work and friendship with the Twentieth Century’s leading composers, I found myself staring at the actual telegrams in which Shostakovich and his Soviet handlers arranged for the American performance of the Seventh Symphony, the “Leningrad” Symphony. They were badly yellowed and even more poorly spelled – but here was the evidence I’d sought.

Now I needed to get the Soviet end of the story. The American material gave me the names of the Russian officials who’d been involved with the microfilm transfer and some dates to work with. I hired a Russian friend of mine to hunt down the leads at the State Archives in Moscow. We used Skype together to clarify exactly what would be useful, what would likely be where.

A couple of the documents in New York were missing pieces, likely torn off during the McCarthy years when even the most patriotic WWII collaborations with Russian agencies were frowned upon. On one 1942 document discussing the microfilm transfer, the name of the addressee had been ripped off in two places. Another was missing its first page. We could tell we’d struck paydirt when we found a full copy of one of these memos sitting in a file folder in Moscow. We’d found our connection, our paper trail that led across the ocean, the desert, and the Russian steppe.

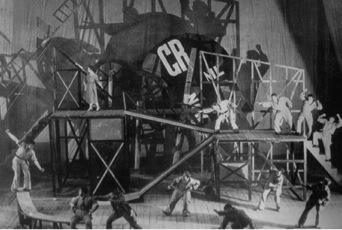

Now that I had some firm names and dates, the weird and fascinating discoveries started rolling in. The priceless microfilm package had almost been lost twice – once when it never reached the American Ambassador on his Pan Am flight home, and once when an agent, stepping into the bathroom, left it on a table where it was picked up by a restaurant busboy and almost thrown in the trash. The conductor featured in Disney’s Fantasia had tried to make a sort of wartime, pro-Soviet Fantasia using Shostakovich’s music and scenes of Russian proletarian life. Even more oddly, William Faulkner had written a (terrible) movie script about the Shostakovich symphony, and Howard Hawks had tried to film it. A nightclub dancer had proposed a strip-tease to the symphony’s invasion theme. Soon, I had almost too much information.

I put all of this material in two forms. In the final book for teens, which I titled Symphony for the City of the Dead: Dmitri Shostakovich and the Siege of Leningrad (Candlewick 2015), the business of the microfilm transfer and the American premiere of the work only take up a few pages. The rest, I put into an academic article (“The Flight of the Seventh: The Voyage of Dmitri Shostakovich’s ‘Leningrad’ Symphony to the West”). The academic article, to my surprise, was therefore a way of backing up the book for teens.

I can’t say how many ways working on this project has both deepened and broadened my understanding of the world and the history of the Twentieth Century. And this is why nonfiction is so great. We hear something as a little anecdote – and when we look into it, either as researchers or as readers, we find there’s a whole world there to discover.

This material may not be used without the express written consent of M.T. Anderson.

Listen to M.T. Anderson tell the story of his name.

Listen to M.T. Anderson tell the story of his name.

Access all of TeachingBooks.net’s online resources about M.T. Anderson and his books.

Leave a Reply